2024

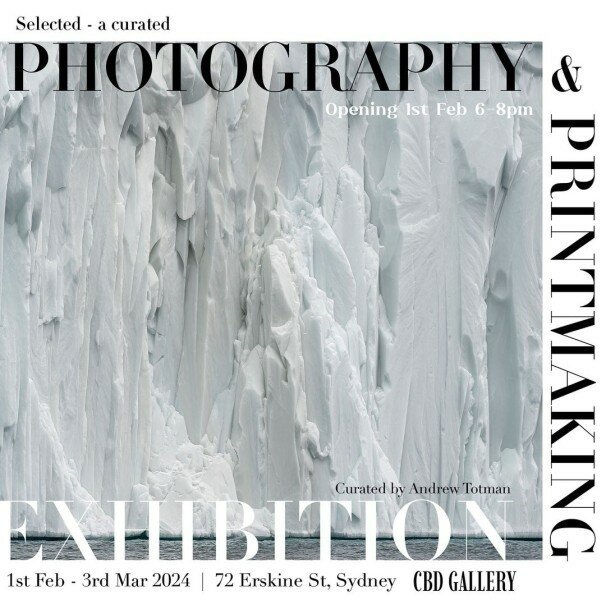

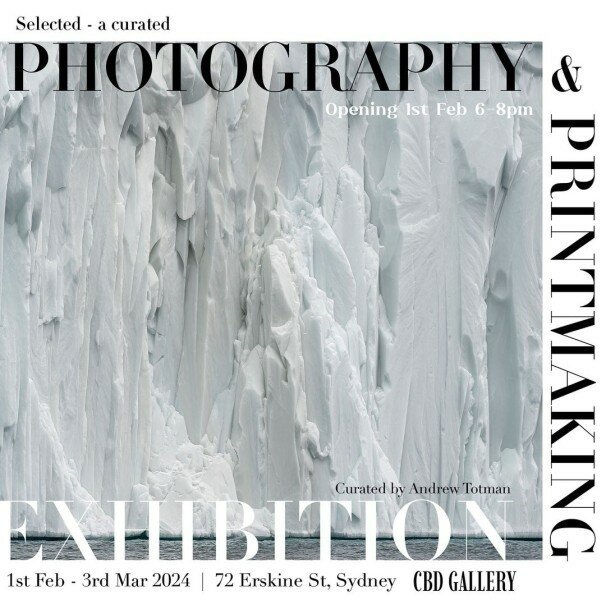

PHOTOGRAPHY & PRINTMAKING exhibition at the CBD Gallery, Sydney

1 February – 3 March

Selected is an opportunity to see into the practice of 22 contemporary artist exploring and thriving in using the medias of Printmaking and Photography across 52 images on display. Although printmaking and photography both originated from discrete technologies for example armour engraving for etching and camera Obscura for photography. They both could be seen to promote the same objective, the desire to replicate a vision of reality in multiples for commercial, political or journalistic ends. Whilst the objective of both disciplines is to leave a trace albeit figure, landscape or still life, the two had been used differently in the art world until the point when they were brought together.

2023

WEST OF CENTRAL at Bathurst Regional Art Gallery

1 July – 27 August

Home to an increasing cohort of contemporary artists and creatives seeking connection, respite, and balance, regional Australia is a place where artists have space to create, experiment, respond and challenge. This exhibition showcases the work of 17 regionally based artists who choose to make work on Wiradjuri Country in the Central Tablelands of NSW.

Of primary concern is the impact of man-made and climactic events on the ecologies and landscape of the region. A chaptered exhibition, to recur over multiple iterations, it celebrates artists who choose to live and work regionally, beyond an urban-centric ‘centre’ and in so doing resituate the regional as a core tenet of their practice.

From the Blue Mountains to Mudgee, Bathurst to Hill End and their surrounds, West of Central featured artists include Aleshia Lonsdale, Anne Graham, Bill Moseley, Blak Douglas, Caitlin Graham, Georgina Pollard, Genevieve Carroll, Dan Kojta, Jason Wing, Joyce Hinterding and David Haines, June Golland, Karla Dickens, Leo Cremonese, Maddison Gibbs, Nicole Welch, and Vicky Browne.

The Art of Analogue Part 1

It was a generous and warm gesture (welcome to Hill End!) when artist, photographer and generally cool person Bill Moseley asked me to talk about how I use an analogue process in unison with digital technologies. Intrigued? Click on the link below.

The Art of Analogue Part 1

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-GrTn4Y1sc

“A presentation on making wet-plate collodion images, aka ‘tintypes’ in the historic town of Hill End. A town well know through the 1870’s Holtermann collection of glass plate negatives. In it, Bill Moseley explains the process and it’s context within on the world of Analogue. The video also features the work of Nicole Welch, and her comments on the significance of the analogue approach to art making.”

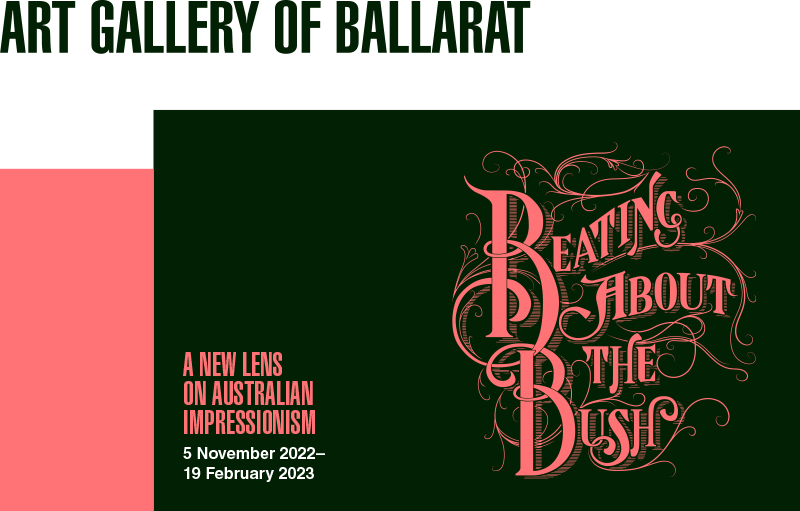

Beating About The Bush at the Art Gallery of Ballarat

November 5 – 19 February 2023

I’m honoured to have my work exhibited in Beating About The Bush at the Art Gallery of Ballarat which puts works of the Australian Impressionism era alongside works by contemporary Australian women photographers. Themes such as gender, hardship of life in the bush, immigration, urban growth, environmental concerns and the presence of Indigenous peoples are explored through the work of some of Australia’s most exciting contemporary artists.

It includes paintings from the past alongside contemporary photography: Donna Bailey, Jane Burton, Peta Clancy, Maree Clarke, Nici Cumpston, Tamara Dean, Fiona Foley, Deanne Gilson, Siri Hayes, Dianne Jones, Leah King-Smith, Rosemary Laing, Janet Laurence, Hayley Millar Baker, Jill Orr, Polixeni Papapetrou, Robyn Stacey, Jacqui Stockdale, Nicole Welch, Anne Zahalka

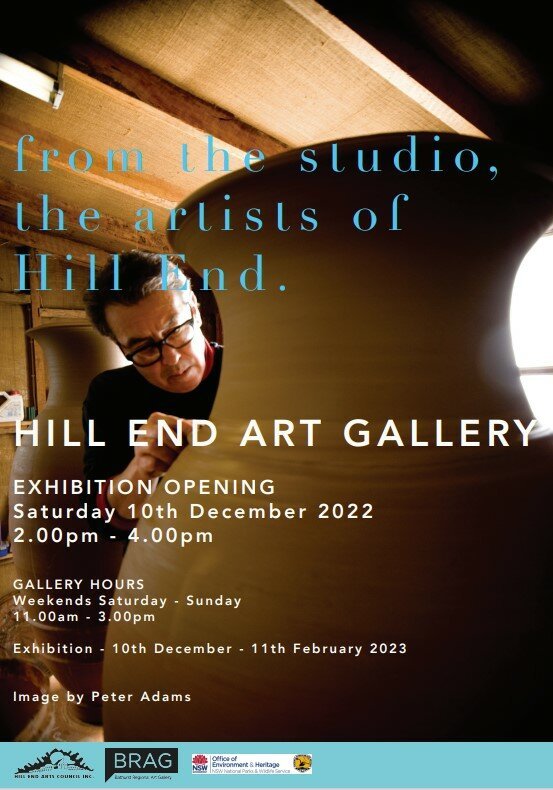

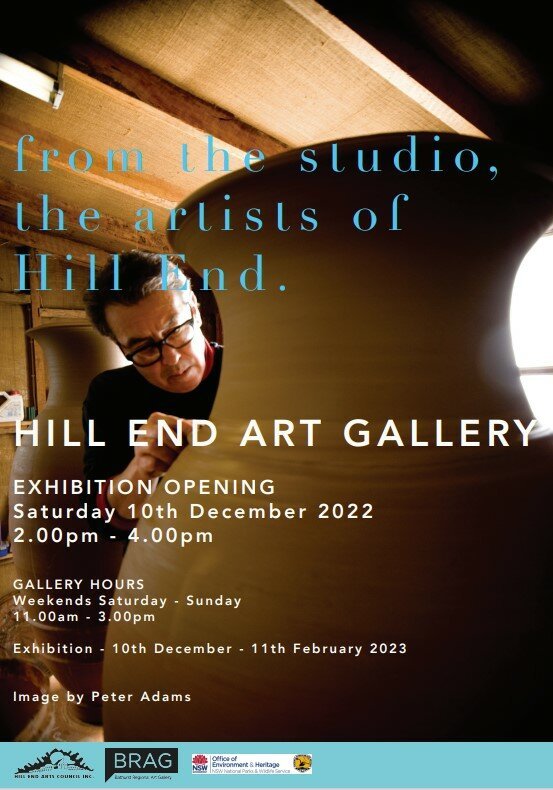

From the Studio, the Artists of Hill End

December to February 2023

A diverse range of artistic practices have flourished and continue to flourish in Hill End. I’m delighted to have an artwork in the group exhibition ’From the studio’, a window into the current artists residing in Hill End and their work.

2022

How a new art project in Bathurst is embracing the many identities of the town – ‘Wiradyuri Ngayirr Ngurambang – Sacred Country’ review in The Conversation by Suzie Gibson

“The most breathtaking project launched at the Mountain Tales event is Aunty Leanna/Wirribee and Nicole Welch’s collaboration with Smith, Wiradyuri Ngayirr Ngurambang – Sacred Country, a film emblazoned across Tremain’s Mill.”

LINK

https://theconversation.com/how-a-new-art-project-in-bathurst-is-embracing-the-many-identities-of-the-town-185860

Bathurst Winter Festival – Tremains Mill Bathurst

‘Wiradyuri Ngayirr Ngurambang – Sacred Country’ July 2022

Nicole Welch, Wiradyuri Elder Wirribee Leanna Carr-Smith, & Kate Smith.

An immersive moving image work exploring Wiradyuri Ngurambang Ngayirr. Wiradyuri Elder Wirribee shares part of the narrative of Custodianship of Country, collaboratively working with local Artist Nicole Welch’s work that is linked to care-taking the environment. This work explores shared understandings between First Nation and Non-First Nation women. Connecting to the landscape from Tarana along the Wambuul/Macquarie River to Wahluu/Mt. Panorama offering a space for contemplation toward a healing of people, community, place,and shared stories.

Yarrahapinni screening at the South Australian Museum

18 February 2022

Delighted that my work ‘Yarrahapinni’ 2019 is screening at the South Australian Museum Night Lab BEDTIME STORIES for the 2022 Adelaide Fringe

“You are about to enter another dimension, a dimension not only

of sight and sound but of mind, a journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination.”

2021

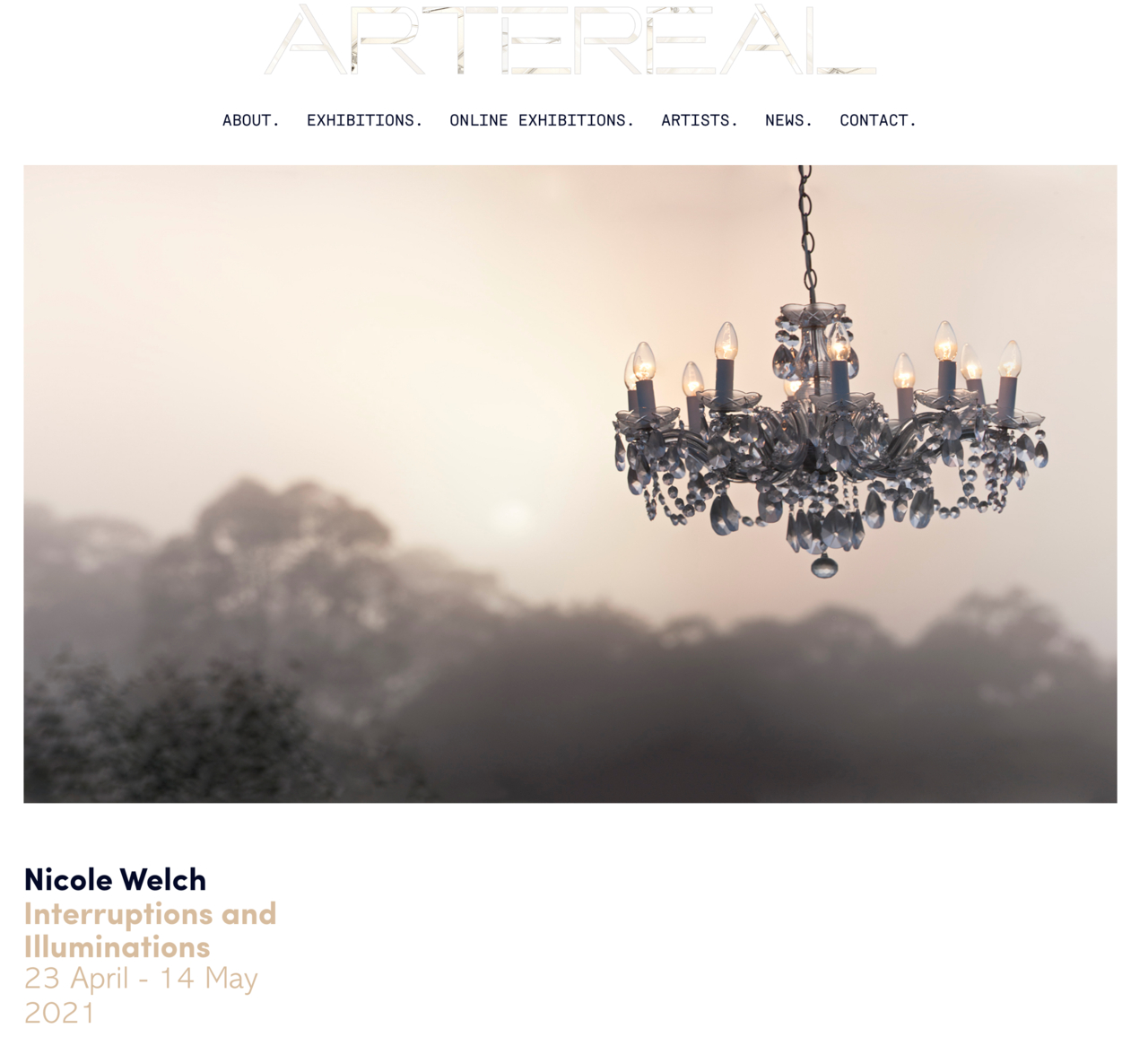

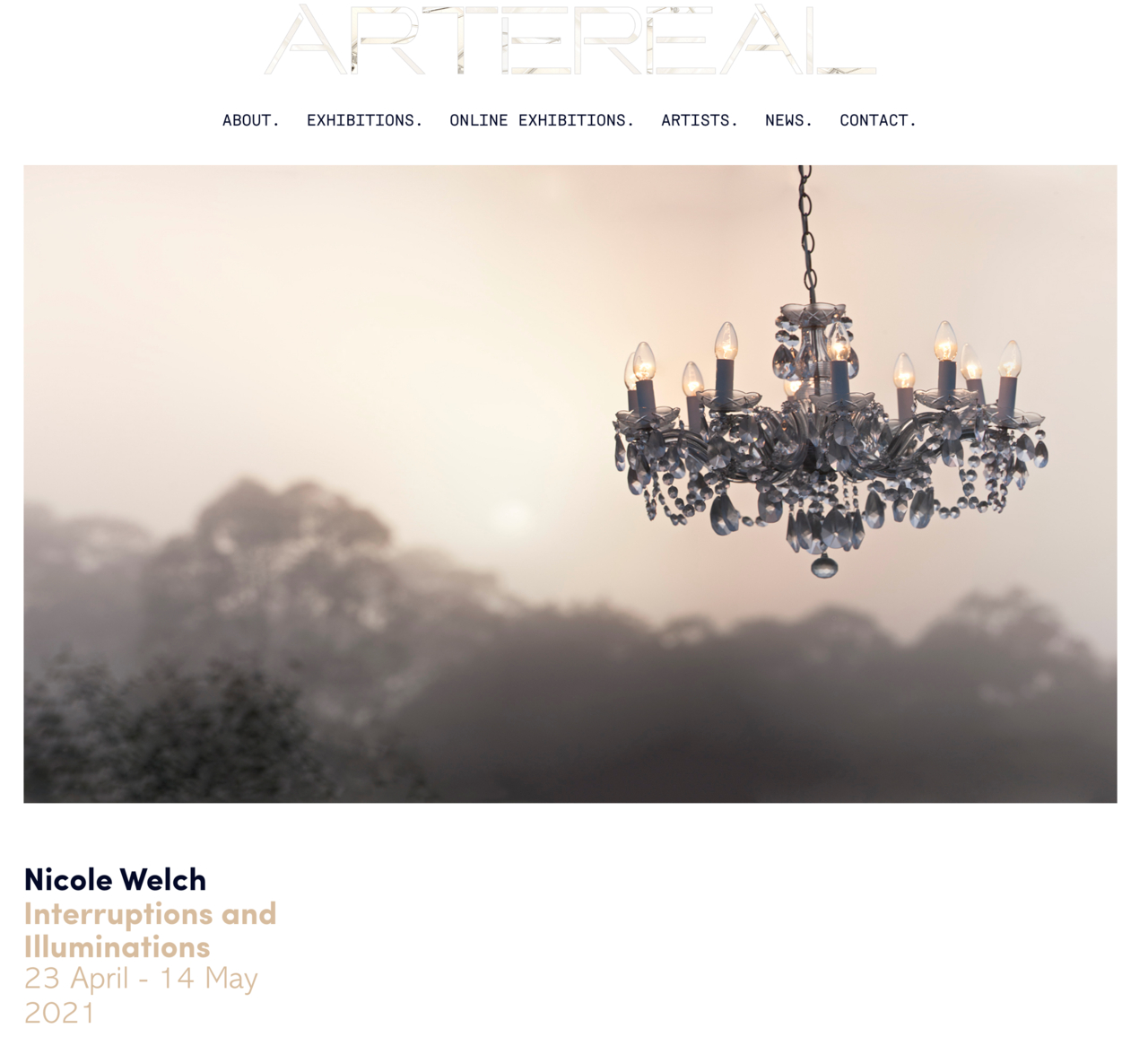

Nicole Welch

Interruptions and Illuminations

23 April – 14 May 2021

Artereal Gallery is excited to present Nicole Welch’s first online show with the gallery – a survey of select artworks produced over the last decade which encapsulate the essence of her practice.

LINK

https://artereal.com.au/online-exhibition/interruptions-and-illuminations/

Time Travel and Digital Art: How Nicole Welch’s Time-lapse Video Art Collapses Time – Agora Digital London – Elizabeth Harris | Ed Kiran Sajan

Making art does make me feel like a time traveller.

Thank you Agora Digital London, Elizabeth Harris and Kiran Sajan for this insight into my ongoing exploration of timelapse film, landscape and body. Agora Digital Art expands awareness of women in digital art – by profiling artists, sharing stories, offering virtual residencies and delivering talks.

Click on the LINK below to read the article

LINK

https://agoradigital.art/time-travel-and-digital-art-how-nicole-welchs-time-lapse-video-art-collapses-time/?fbclid=IwAR2TvQkkxQ2cDbDIDbP7_WC2ZR-u2_kX-HtX2bIckC5myp5xlNiJ96lXJ6I

REGIONAL ARTS FUND GRANT 2021 - REGIONAL ARTS NSW

Delighted that my future project AS ABOVE SO BELOW has been generously supported through the Regional Arts Fund – Regional Arts NSW.

“Artist Nicole Welch will record in photography and moving image her reconnection to the natural world in response to ongoing isolation imposed by COVID-19. She will develop new techniques through the exploration of macro and micro photography to make new installations and performances for her LAND & BODY series of work, across sites at the Macquarie and the Lachlan Rivers. The outcomes of AS ABOVE, SO BELOW will be exhibited at the Orange Regional Gallery and MAY SPACE Sydney.”

・・・

Congratulations to the 18 artists and organisations who have received RAF project funding to support new projects across NSW in 2021! RANSW CEO, Elizabeth Rogers said: ” Once again, the calibre of these projects supported by the Regional Arts Fund in NSW showcases the creativity of our regional arts organisations from across the state.”

2020

The CORRIDOR Project Artist Residency 2020 (November)

Just home from a special kind of isolation at the CORRIDOR Project at Darby Falls near Cowra NSW undertaking an artist residency.

The CORRIDOR project is a multidisciplinary arts organisation located in regional NSW Australia. The 2020-2021 Arts and Science program links arts & culture and science, through residencies; events and workshops.

I am extremely grateful to the CORRIDOR project manager Phoebe Cowdery, the CORRIDOR patrons Andrew Upton and Cate Blanchett, the Orange Regional Gallery and the various funding bodies that have supported the residency program for 2020.

SYDNEY CONTEMPORARY PRESENTS 2020 • MAY SPACE

I’m grateful to be presenting my moving image work Yarrahapinni at Sydney Contemporary’s first online fair with MAY SPACE - alongside the wonderful Todd Fuller, Mylyn Nguyen, Catherine O’Donnell, Janet Tavener and Loribelle Spirovski.

See this link for full access to the 450 artworks, 380 artists, and 90 galleries participating this year!

https://sydneycontemporary.com.au/scpresents/

!!

Yarrahapinni (preview) 2019

single channel HD infrared time lapse – 3:21mins

50 inch screen, gilded frame edition of 3

The CORRIDOR artist-in-residency program 2020 (May)

The last morning of my preliminary artist residency in complete blissed out isolation at the CORRIDOR PROJECT in the Central West of New South Wales as part of the CORRIDOR artist-in-residency program 2020. The dramatic change in the landscape and natures resilience is inspiring to me – so green after such a long dry spell. It has been an invaluable time to explore new media, techniques and ideas for a new body of work to be exhibited at the Orange Regional Gallery – a welcomed break from home ISO - it has started a ball rolling, thank you

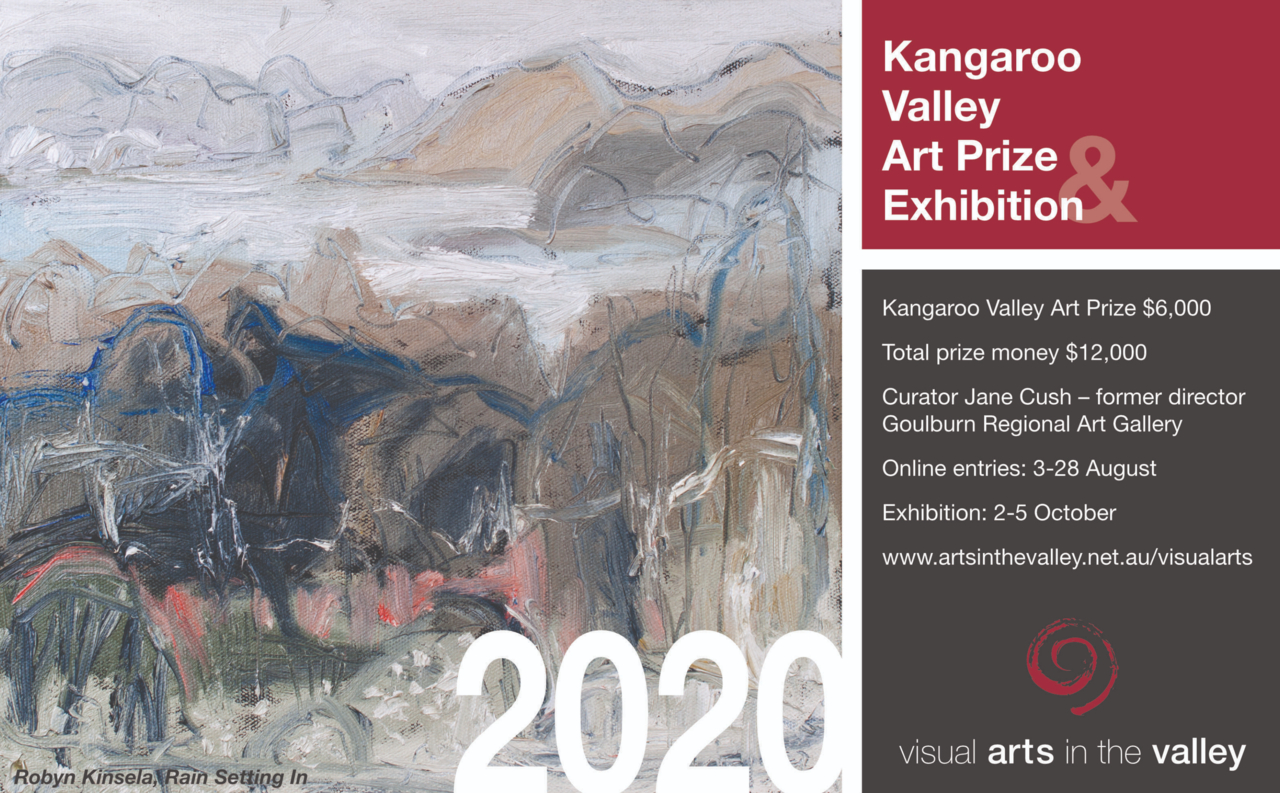

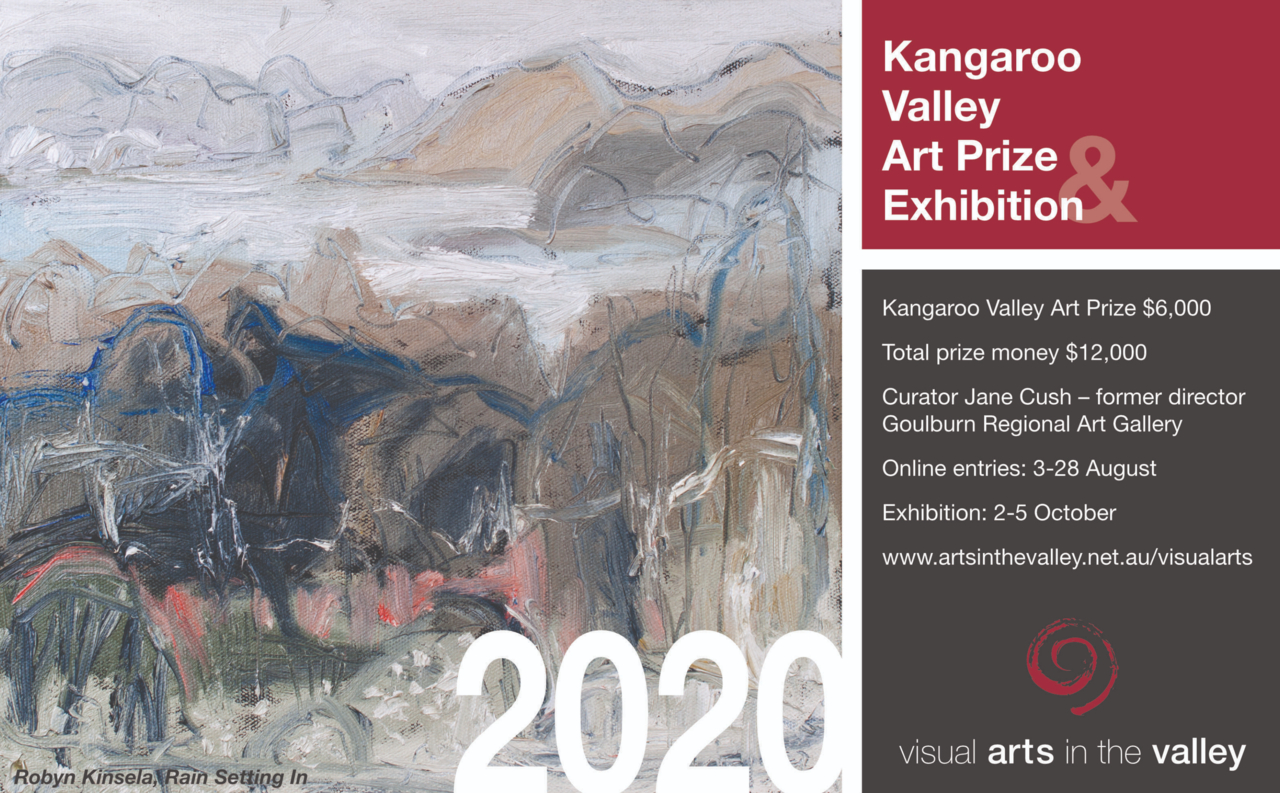

Kangaroo Valley Art Prize

The moving image work Yarrahapinni has been selected as a finalist in the Kangaroo Valley Art Prize.

ArtsHub Review by Gina Fairley

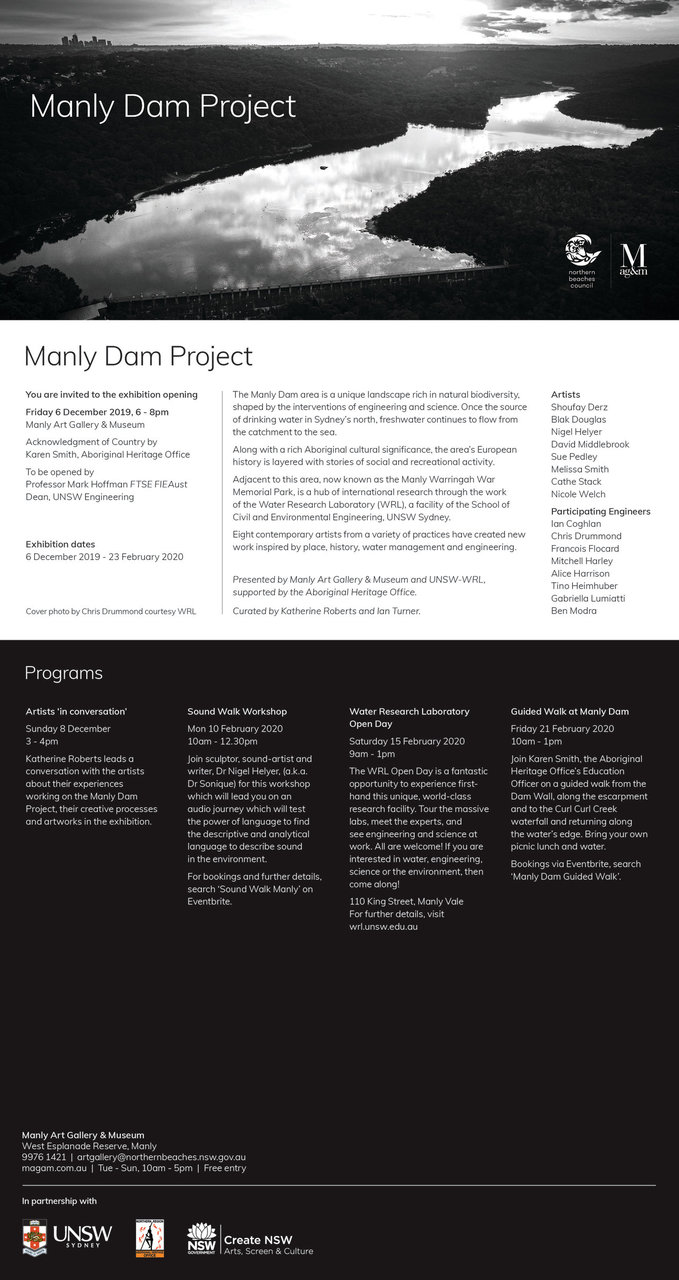

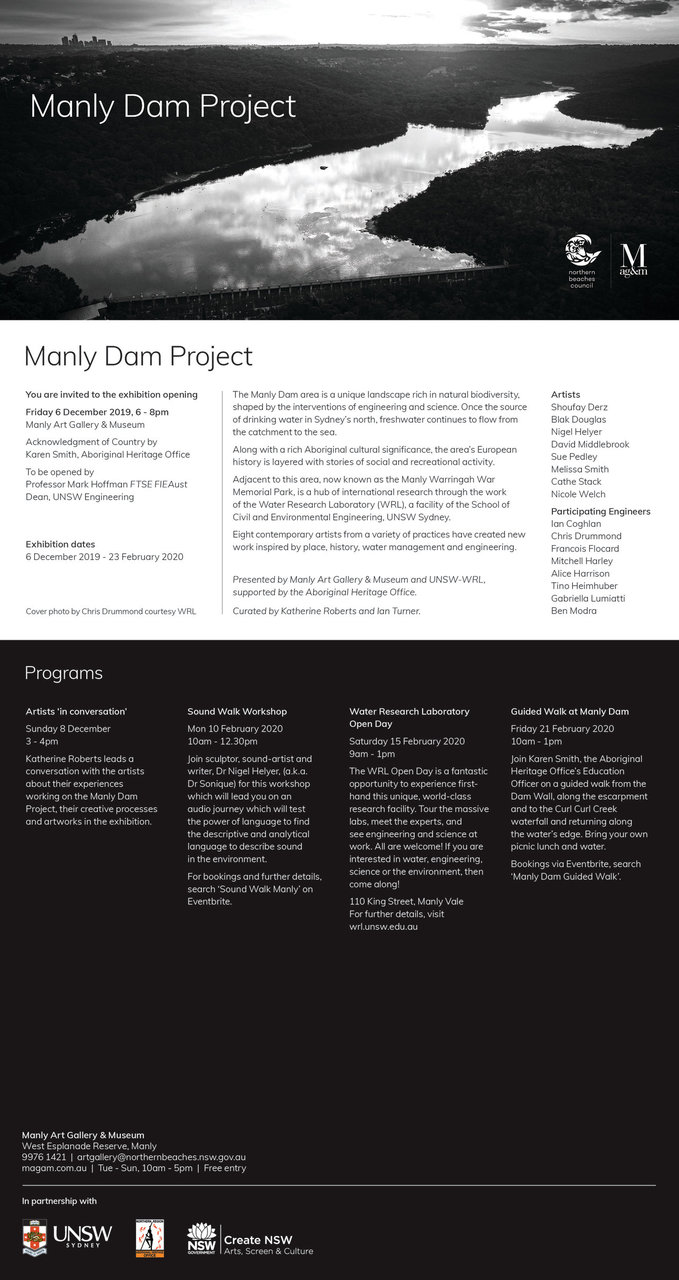

Manly Dam Project

Manly Art Gallery (NSW)

LINK

https://visual.artshub.com.au/news-article/reviews/visual-arts/gina-fairley/manly-dam-project-manly-art-gallery-nsw-259532?fbclid=IwAR2CB3gSZnylmOJt96wJzPKfWMiKPmMryygPvJFN5ZyXi2HSEHk-bcob1vI

Listening to the Anthropocene

Yarrahapinni has been selected/peer reviewed for the 2020, Charles Sturt University Creative Practice Circle symposium and exhibition entitled Listening in the Anthropocene: Creative practice and multimedia artsmaking in response to a human influenced world.

2019

Manly Dam Project

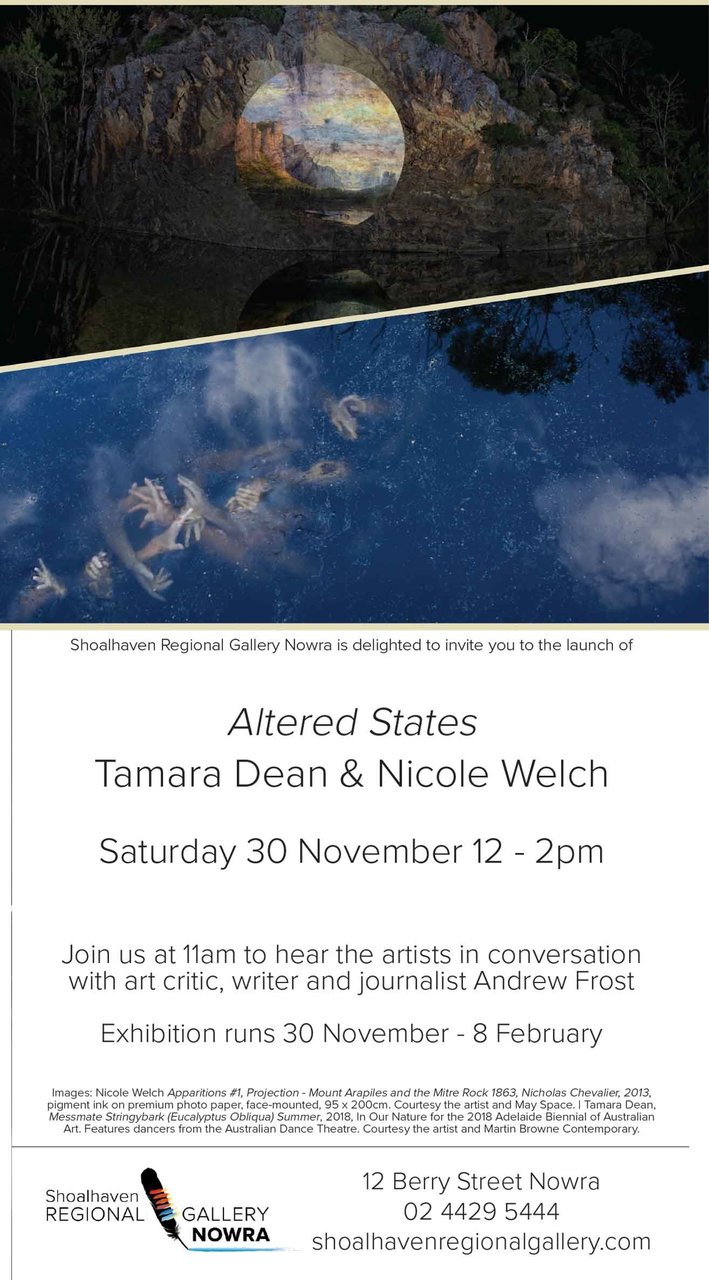

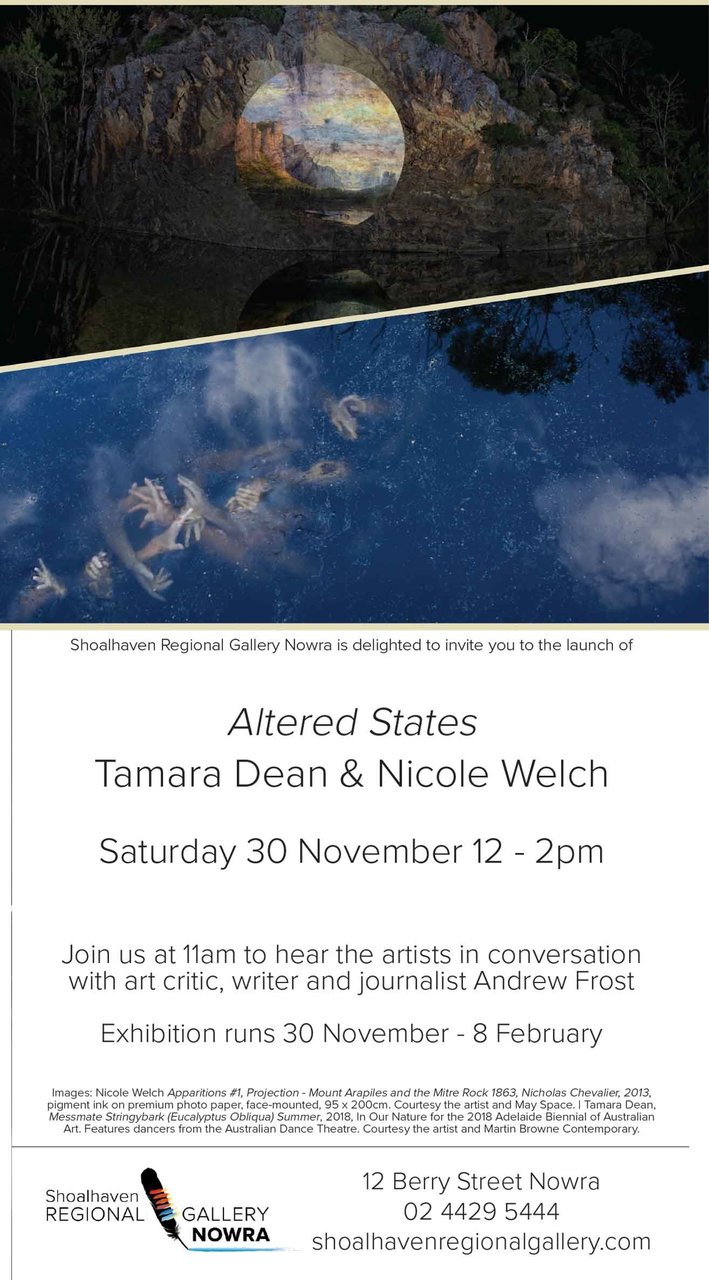

Altered States – Tamara Dean & Nicole Welch

Naked & Nude Art Prize

TRANSFORMATION selected as a finalist in the Naked & Nude Art Prize at the Manning Regional Art Gallery.

Sydney Contemporary Art Fair 2019

New work ‘W I L D #1 – prelude’ exhibited at the MAY SPACE booth, G09

Stillness & Motion – Nicole Welch – Adelaide Perry Gallery

Select photographic works and film from the past 5 years.

2 – 24 May 2019

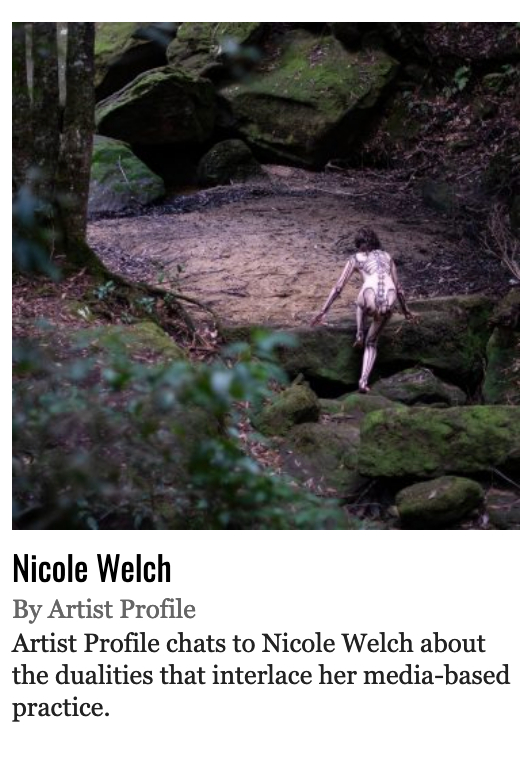

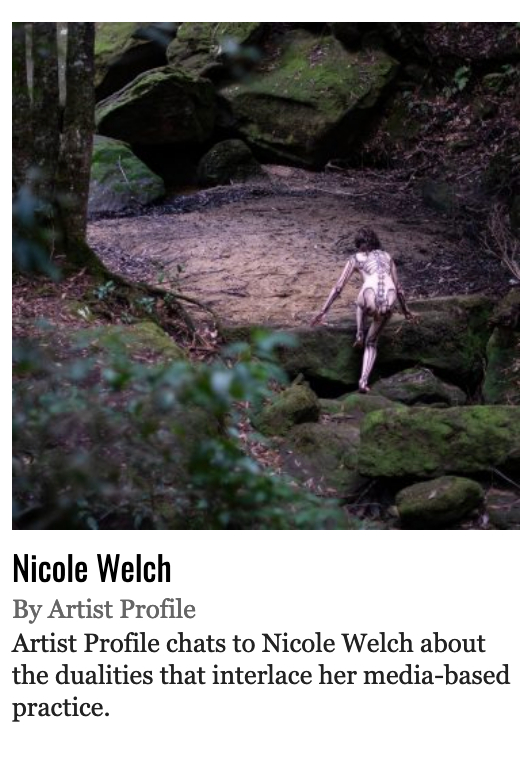

Nicole Welch By Artist Profile

LINK

https://www.artistprofile.com.au/nicole-welch/

2018

Making it as a regional artist – the realities and the wins

ArtsHub visual arts editor Gina Fairley’s feature editorial on Nicole Welch for ArtState Bathurst

Transformation – arrival, installed at Tremains Mill for ArtState Bathurst 2018

LINK

https://visual.artshub.com.au/news-article/features/visual-arts/gina-fairley/making-it-as-a-regional-artist-the-realities-and-the-wins-256839?utm_source=ArtsHub+Australia&utm_campaign=94d6aaf38a-UA-828966-1&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_2a8ea75e81-94d6aaf38a-304113053&fbclid=IwAR0TLXyOknKMReZDiSmTininEpoQzMUx_tPjD53llAkUd4W-opQEluYa9jo

5th International Motion Festival, Cyprus

The time-lapse film Wildēornes Body has been selected for the 5th International Motion Festival, Cyprus. It will feature in the Single Channel Show (Video Art presented with single channel works. Experiments pushing the limits of the moving image)

Wildēornes Body (still) 2017

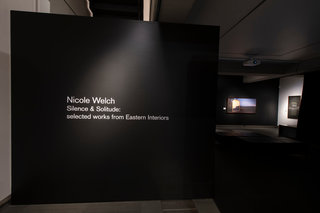

Nicole Welch – Black Box Projects 2018

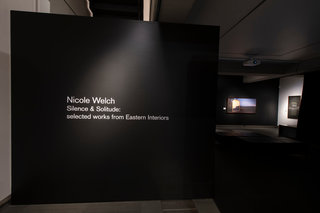

To coincide with Nicole Welch’s presentation of the moving image work Transformation and photographic series Mementos at Artstate Bathurst (1 to 4 November 2018), as well as her solo exhibition Silence & Solitude: select works from Eastern Interiors at Glasshouse Regional Gallery (12 October to 2 December 2018), MAY SPACE is presenting a selection of Welch’s video artworks in Black Box Projects.

Transformation: the prelude (preview)

TRANSFORMATION unveiled at ArtState Bathurst 2018

Nicole Welch’s most ambitious project to date was a featured part of Artstate Bathurst 2018. The two-channel video work sees a female figure carefully moving through the landscape.

Transformation – journey, installed at Tremains Mill for ArtState Bathurst, 2018

MEMENTOS ArtState Bathurst 2018

Nicole Welch was chosen to create a small gift for the delegates that attended Artstate Bathurst 2018. The resulting series of infrared photographs were packaged up in miniature for the guests. Full-scale versions are now available from MAY SPACE.

Mementos #3 – Macquarie River 2018

LINK

https://www.mayspace.com.au/exhibitions-details/nicole-welch-artstate-bathurst

ArtsHub Review by Helen Wyatt

Review: Jason Wing and Nicole Welch, 4.5 stars, Glasshouse Regional Gallery

Silence & Solitude: select works from Eastern Interiors

GlassHouse Regional Gallery, Port Macquarie

Silence & Solitude exhibition at GlassHouse Regional Gallery

LINK

https://visual.artshub.com.au/news-article/reviews/visual-arts/helen-wyatt/review-jason-wing-and-nicole-welch-glasshouse-regional-gallery-256707?fbclid=IwAR0g8PuwkcQ2unOv13l2bM1MLLG9zGF6sC4Irex4TzE8Pz_R7QcQaUD83_k

Media artist Nicole Welch explores the colonial history of the Blue Mountains in exhibition at The Glasshouse

Port Macquarie News

Nicole Welch at the GlassHouse Regional Gallery 2018

LINK

https://www.portnews.com.au/story/5699463/silence-and-solitude-exhibition-reflects-on-colonial-past/?fbclid=IwAR2zdbJTsz0B6nBMwIxH63HfMTU2ZtMRSOYZxeeJg_nQgcZMiTR9xJWhUXA

Transformed by Place: Q&A with Artstate Artist Nicole Welch

An interview with Nicole Welch about TRANSFORMATION and MEMENTOS commissioned for ArtState NSW 2018

LINK

http://www.artstate.com.au/transformed-by-place-qa-with-artstate-artist-nicole-welch/

Finalist Grace Cossington Smith Art Prize 2018

Three photographs from the Wildēornes Land series have been selected for the Grace Cossington Smith Art Prize 2018

Wildēornes Land #1 – Capertee Valley 2017

Wildēornes Land #3 – Grose Valley 2017

Wildēornes Land #7 – Wollemi 2017!

ArtState Bathurst 2018

Nicole Welch is producing two new works TRANSFORMATION and MEMENTOS for ArtState Bathurst NSW Regional Arts Conference, Create NSW, 2018

Transformation: the prelude screened at Sydney Contemporary Art Fair 2018

Nicole Welchs latest moving image work Transformation : the prelude was unvieled at the Sydney Contemporary Art Fair 2018. Constructed from 1000 photographs of a waterfall captured using infrared technology, the resulting hyperreal light spectrum and colours revealed are invisible to the human eye, symbolically referencing the notion of the unobserved

Transformation: the prelude (preview)

2017 + PRIOR

WILDĒORNES LAND 2017

Wildēornes Land

by Dr. Ann Finegan

Co-Director Cementa Contemporary Arts Festival

Interrogations of European notions of the sublime in nature, colonialist mastery and ecology subtend the cinematic imaginary of Nicole Welch. In Wildēornes Land she subverts another Eurocentric concept brought to Australian shores: the wilderness of European folklore. Steeped in the dark lore of the forest – its haunted zones, domains of witches, its dens of wolves and shapeshifters – European folktales persist in many of the stories handed down. The Brothers Grimm, Hansel and Gretel, Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Riding Hood. When the European colonists arrived in Australia they also brought with them this dark imagery. Deep in the European psyche, bad things happen to people in the woods. The wilderness is therefore the place that you don’t go – certainly not unarmed or lacking talismans. It is a place of extreme vulnerability. Even for Indigenous Australians there are places of bad spirits, places that command ceremonies of appeasement. Unless, of course, you are on a peak, looking down, surveying the vastness of the scary place from the other side of a magical divide.

The importance of the vantage point cannot be underestimated. Without it, the vast and daunting scale of the ‘Wildēornes’ cannot be enjoyed through the European colonialist lens. The vantage point, drawing its line of demarcation between known and unknown, savage and civilized, safe and unsafe, underlies the lesson of the sublime in nature: terrifying chasms and dangers tamed through the imaginary possession of the view from on high, from that point of Kantian safety. In Wildēornes Land something has shifted. Nature is no longer secure. With climate change the big scary wilderness has lost its power. Welch, naked, in an antique mourning shawl, stands on a sublime Blue Mountains abyss. She occupies the same position as Caspar David Friedrich’s confident wanderer, immaculate in his 18th century gentleman’s suit, surveying a mighty realm. Welch, by contrast, in mourning garb, offers herself, naked and sacrificial, to a world on the brink of being lost. The symbolism of Welch’s composition asks us to imagine the unimaginable: an ecological crisis that dwarfs the wilderness that was, once, for Europeans, our deepest repository of fear. Across images of clouds and sky, at cinematic scale, that same delicate black mourning shawl suspends itself, its pall a symbol of human making heralding death. It epitomises the Victorian era as the departure point from which the industrial revolution and the burning of fossil fuels accelerated. Like the gaseous changes taking place in the atmosphere there’s a gossamer lightness to it.

Tondo #4, Projection – Regent Honeyeater from ‘The Birds of Australia: in seven volumes’, John Gould, 1848, 2016

In the tondi, exquisitely framing the landscape through the circular aperture of an 18th century aesthetic, something is clearly wrong. The sky dominates. It’s as if there’s been an accident, someone has bumped the camera, skewing the subject. Instead of rare birds holding the focus in Tondo #4, Projection – Regent Honeyeater (2016), or the view from the lookout garnering attention, Tondo #3, Kanangra Wall Lookout (2014), the sky intrudes at odd angles, somehow menacing. Where the wilderness once dominated, lurking in the psyche, the carbon-saturated atmosphere has become the new sublime of danger.

Artlink Review

Nicole Welch: Wildēornes Land

Blue Mountains Cultural Centre

Wildēornes Land installed at the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre City Gallery 2017

LINK

https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4590/nicole-welch-wildC493ornes-land/

EASTERN INTERIORS: EXPLORATIONS FROM BATHURST TO ALBURY 2015

Forward Reflections

by Olivia Welch (not related to the artist)

Notions of ‘beauty’ and ‘sublimity’ are conjured when encountering the photographic and video work of Nicole Welch. Though it could be instinctive in the twenty-first century to consign the exceptional picturesque appeal of these works to a mastery of digital manipulation, Welch does not depend on such techniques. Instead, the artist traverses through areas of bushland, locating incredible landscapes to create compositions using large-scale projectors, generators, spotlights and research-inspired objects. These works have seen Welch interrupt the rugged terrain with illuminating beams of light, projections of images and a chandelier that is seemingly floating in the landscape, despite actually being hoisted into the scene using a crane. In the suite of images that formulate Eastern Interiors: explorations from Bathurst to Albury new iconography emerges with the inclusion of an antique mirror and the use of text.

There is an archival foundation to Welch’s hybrid imagery. The landscapes within her photographs do not simply exist as visually attractive images, but engage with the history of ‘landscape’ as a creative genre, whilst also integrating interpretations of the land from literature, exploration records and other resources. Her series Illumination featured a luminescent Victorian-style chandelier, taking cues from archival research into the historic Holtermann Collection; a series of photographs made by Beaufoy Merlin and Charles Bayliss in 1872. Welch’s 2014 body of work Apparitions featured circular details of paintings from the Romantic period, found in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia and the Art Gallery of New South Wales, projected onto waterside cliffs and foggy forest scenery. Eastern Interiors: explorations from Bathurst to Albury references Explorer Thomas Mitchell’s journals originally published in 1838 under the title ‘Three expeditions into the interior of Eastern Australia’, a first edition of which can be found in the collection of the State Library of New South Wales. Mitchell was the Surveyor General of New South Wales and his role was to manage and administer Crown Land; defining boundaries, locating places for new settlements and planning routes for transportation. This job entailed lengthy expeditions across the country, often requiring the assistance of Indigenous guides. Through these journeys, land was divided and defined by the colonial settlers in ways that suited their Eurocentric needs and opinions. These decisions and descriptions shape our knowledge, understanding and perception of the land today, a theme that Welch aptly draws attention to.

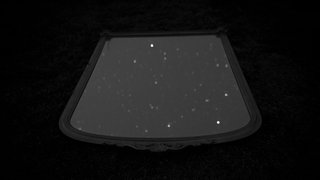

Comparably to Mitchell, Welch embarked on a cross-state expedition in order to (re)discover the locations within her latest series of work. Informing the suite is a residency the artist completed in September of 2014 at Hill End near Bathurst, as well as time spent in and around Albury in the State’s south. The video work that completes this series, titled ‘East West’, references the travelling nature of Welch’s research, as well as the explorers she quotes. It features a mirror reflecting the sky as it transitions from day to night, communicating the role of the sky as a global and perpetual navigational device.

East West (still) time-lapse film 2015

East West (still) time-lapse film 2015

Welch is originally from Bathurst and is currently based there, making her connection both personal and physical. A group of works in Eastern Interiors: explorations from Bathurst to Albury is titled ‘Frightful Tremendous Pass’. The group takes its name from a 200-year-old quote within Governor Macquarie’s journals that was written while he was travelling to proclaim Bathurst as a settlement of the colony. As the Governor’s journal reads, “At 11 o’clock, (we) reached the termination of the Blue Mountains… to view this frightful tremendous Pass.” In the context of these diaries that also describe one area as “very bad” for cattle and carriages, and the soil quality of Bathurst as “…fit for every purpose of Cultivation and Pasture…”, it is easy to see how these descriptions of the Australian terrain are based upon what was seen as useful and/or beautiful to European needs and preferences.

In the second and third work of the ‘Frightful Tremendous Pass’ set, Welch plays with Governor Mitchell’s accounts. The artist ironically projects Mitchell’s idea of tremendousness and frightfulness via literal projections. The word “Tremendous” is cast onto a plateau girt by water at the edge of the Blue Mountains, and the word “Frightful” is contained within a nocturnal scene, illuminated over a bed of ferns surrounded by tall native trees. These observations powerfully punctuate their respective landscapes, causing associations between the meanings of these words and Welch’s carefully orchestrated environments to merge- revealing the impressionability of such emotive language. Similarly, the set of works titled ‘Silence and Solitude’ is influenced by Governor Macquarie’s following musing: “…the silence and solitude, which reign in a space of such extent and beauty as seems designed by nature for the occupancy and comfort of man, create a degree of melancholy in the mind…” In one of the works, Welch has projected the word “Solitude” onto a misty landscape. This work remains the most sinister image of the suite, ghostly in its effect. With all of these photographs, Welch cleverly embodies both hostile and inviting environments with historical descriptions that label the conditions in which the colonial settlers encountered them.

Taking their titles from words within William Hovel’s journal, which relays his explorations to find new grazing land with Hamilton Hume in 1824, are Welch’s works given the common title ‘Magnificent Prospect’. Describing an impressionable sight of the Snowy Mountains near Albury, Hovell writes, “At the end of seven miles a prospect came in view the most magnificent.” Featuring a mirror reflecting the landscape opposite the scene in which it is situated, these photographs project magnificence in their striking appearance. This set includes an eerie fog-filled scene where the trees seemingly dissolve into an encroaching distance, as well as a brilliant blue sky striped with fluorescent sun-soaked clouds that are disrupted by the reflection of pastel pink heavens glowing behind a rocky cliff. These captivating environments are wondrous, yet diverse, evoking the idea of endless possibilities for Hovell’s new “prospect”, a label that also coveys a sense of adventure and discovery designated to a land not yet captured or claimed.

Though it is easy to relegate notions of Australia being an unclaimed wilderness to an archaic imperialist past, Welch reveals how the consequences of this ideology have seeped into contemporary society’s relationship with the Australian landscape. The artist references a quote from theorist W. J. T. Mitchell’s essay ‘Imperial Landscape’, which reads, “Like all things in a rearview mirror, these landscapes may be closer to us than they appear.” Welch’s works containing mirrors draw from this quote by literally placing a mirror in the landscape. In each work, the reflection is contained within an antique frame that acts like a portal into the past. Through this, Welch exposes the contemporary desire to view the Australian terrain via a nostalgic lens, which romanticises the landscape as an undiscovered place of mystical beauty and inhospitable depths. However, this romantic mythology is ruptured, as the mirror lies within the landscape it reflects, showing that both the evocative view in the frame, and the perceptibly present-day terrain surrounding it, coexist.

Throughout Eastern Interiors: explorations from Bathurst to Albury, the past and present are conflated in singular images and filmic scenes. With this, Welch subtly offers a thoughtful examination on how contemporary perceptions of the natural Australian landscape continue to be shaped and informed by enduring historical ideologies.

APPARITIONS 2014

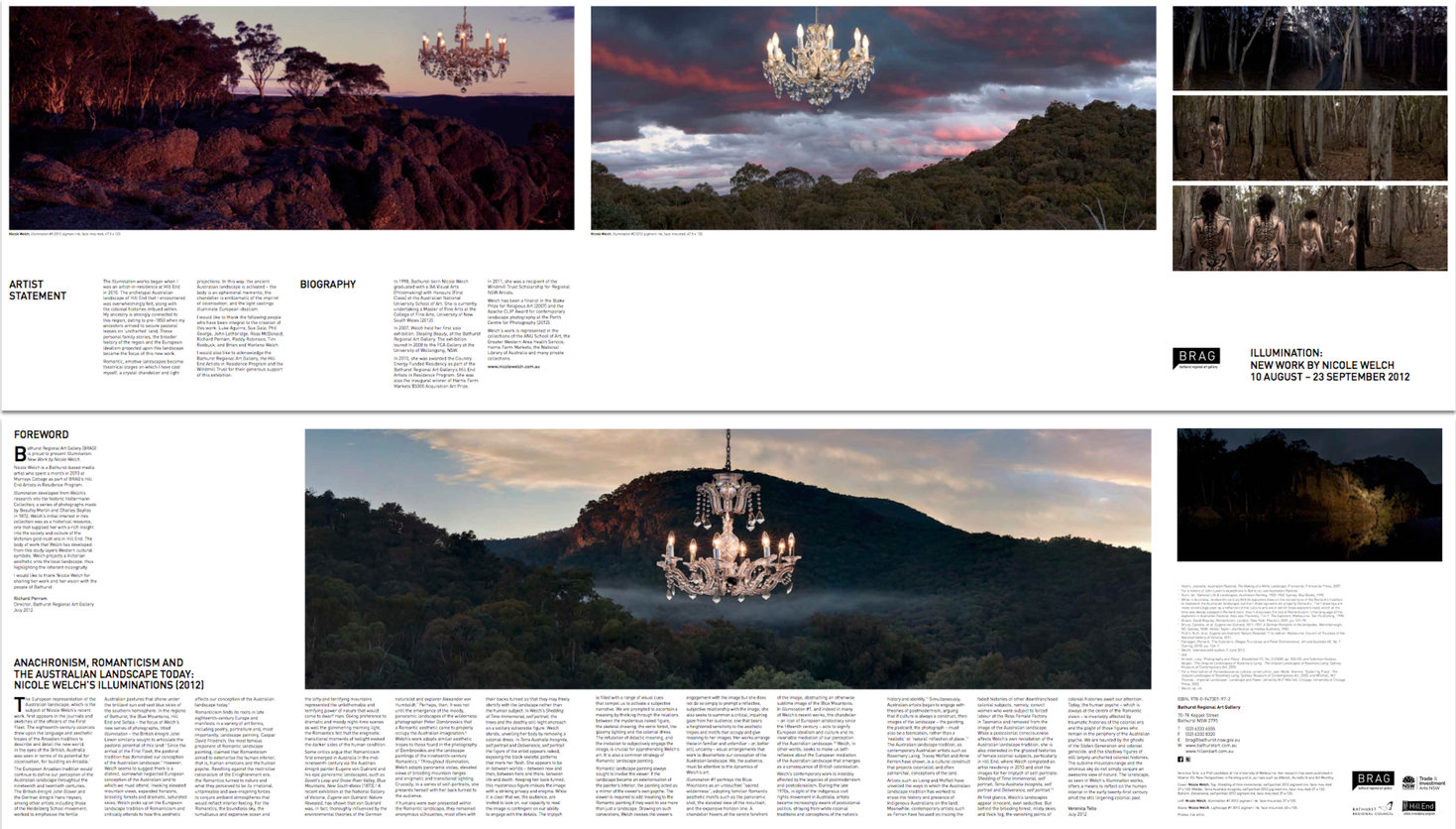

ILLUMINATION 2012

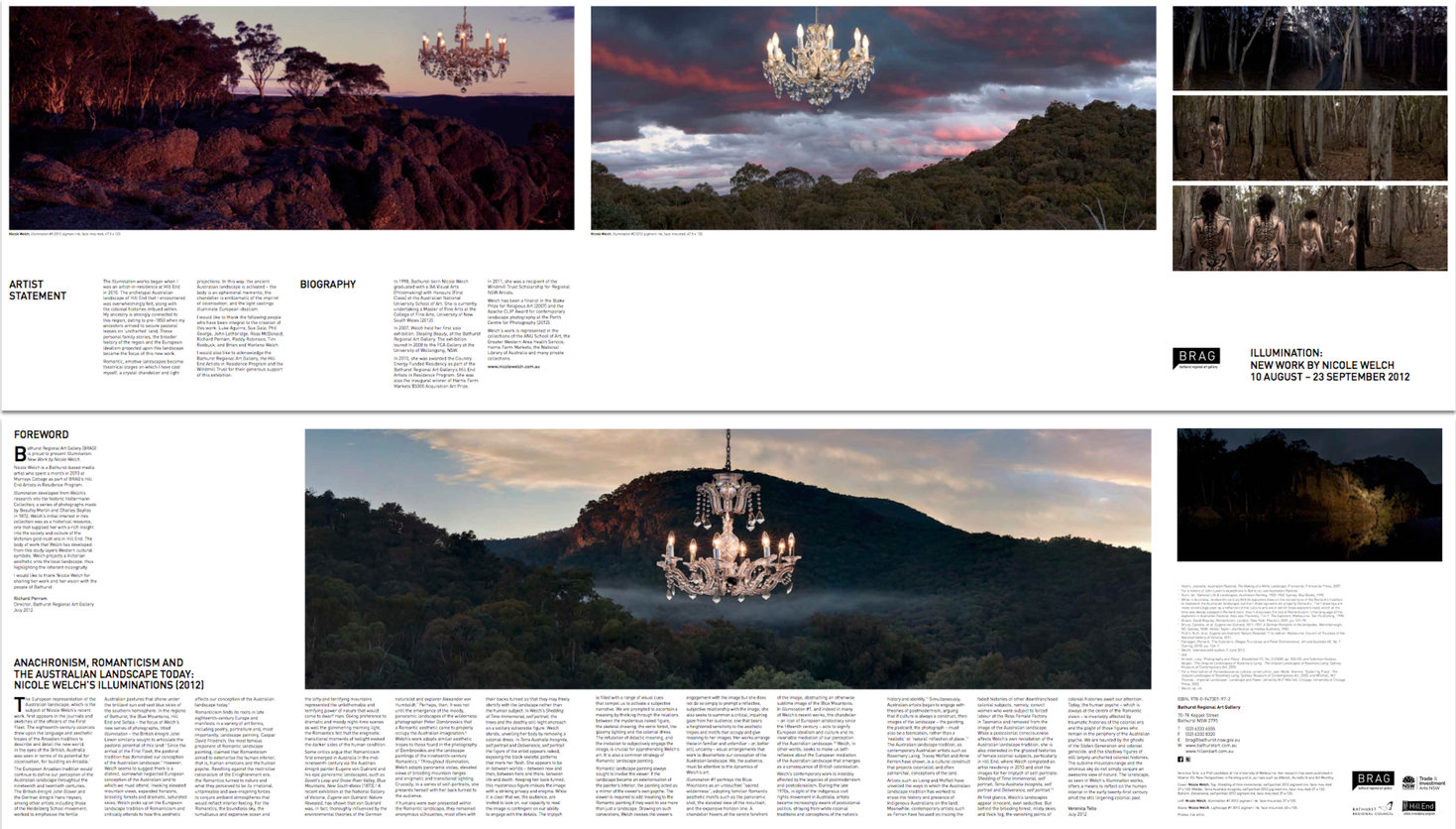

Anachronism, Romanticism and the Australian Landscape Today: Nicole Welch’s Illuminations (2012)*

by Veronica Tello

Terra Australis Incognita from the Self series, Hill End 2010

Deliverance from the Self series, Hill End 2010

The European, colonial, representation of the Australian landscape, which is the subject of Nicole Welch’s recent work, first appears in the journals and sketches of the officers of the First Fleet. These eighteenth century colonialists drew upon the language and aesthetic tropes of the arcadian tradition to describe and detail the new world. Through the eyes of British colonialists, Australia was always seen in terms of its potential for colonisation, for building an arcadia. The European arcadian tradition would continue to define our perception of the Australian landscape throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The British émigré John Glover and the German émigré Hans Heysen, amongst other artists including the Heidelberg School, worked to emphasise the fertile and arcadian Australian pastures, which shone under the brilliant Australian sun and its blue skies. In Bathurst, and the regions of the Blue Mountains, Hill End and Sofala, which are the focus of the landscapes in Welch’s recent work, John Lewin similarly sought to articulate the pastoral potential of this land. Since the arrival of the First Fleet, the pastoral tradition has dominated our conception of the Australian landscape. But as Welch seems to suggest, there is a distinct, somewhat neglected, European conception of the Australian land to which we must attend. Invoking elevated mountain views, expanded horizons, brooding forests and dramatic saturated ominous skies Welch picks up on the European landscape tradition of Romanticism and critically attends to how this aesthetic affects our conception of the Australian landscape today.

The artistic movement of Romanticism finds its roots in late 18th century Europe and manifests in a variety of art forms from poetry to portraiture, and most importantly, landscape painting. As Caspar David Friedrich, the most famous proponent of Romantic landscape painting claimed, via artistic representations, Romanticism aimed to exteriorize the human interior, that is, human emotions and the human psyche. Revolting against the restrictive rationalism of the Enlightenment era, the Romantics turned to nature and what they perceived to be its irrational, untameable and awe-inspiring forces to conjure ambient atmospheres that would reflect interior feeling. For the Romantics, the boundless sky, the tumultuous and expansive ocean, the lofty and terrifying mountains represented the unfathomable and terrifying power of nature that would come to dwarf man. Giving preference to dramatic and moody nighttime scenes as well the glimmering morning light, the Romantics felt that these enigmatic transitional moments of twilight evoked the darker conditions of the human condition.

Some critics argue that Romanticism first emerged in Australia in the mid 19th century via the Austrian émigré painter Eugene Von Guérard and his epic panoramic landscapes, as seen in Govett’s Leap and Grose River Valley, Blue Mountains, New South Wales (1873). But the recent exhibition Eugene Von Geurard: Nature Revealed (National Gallery of Victoria, 2011) has shown that Von Guérard was, in fact, thoroughly influenced by Alexander Von Humboldt’s scientific, rationalising, theories of nature. Perhaps, then, it was not until the emergence of the moody, awe inspiring, panoramic landscapes by the wilderness photographer Peter Dombrovskis that a Romantic aesthetic came to properly occupy the Australian imagination. Welch’s recent art, adopts similar aesthetic tropes to those that are found in the photography of Dombrovksis and the 19th century Romantic landscape painters. Throughout her new series of photographs titled Illuminations, Welch adopts panoramic vistas, an elevated view of a dark brooding mountain range, enigmatic and transitional lighting, and crucially, in a series of self-portraits, she presents herself with her back turned to the audience.

If humans were ever presented within the Romantic landscape, they remained anonymous silhouettes, most often with their backs turned to the viewer, so that she may freely identify with the landscape rather than human subject. In Shedding of Time immemorial the trees and the deathly still night encroach on a solitary vulnerable figure. Welch stands idly unveiling her body and removing a colonial dress. In Terra Australia Incognita and Deliverance, the figure appears naked, exposing the black skeletal patterns that mark her flesh. She appears to be in between worlds – between now and then, between here and there, between life and death. Keeping her back turned to the audience, this mysterious figure imbues these images with a striking privacy and enigma. For while it is clear that we, the audience, are invited to look on, our capacities to read the image are contingent on our abilities to engage its details. The triptych is filled with a range of visual cues that compel us to activate a subjective narrative. We are prompted to ascertain a meaning by thinking through the relations between the mysterious naked figure, the skeletal drawing, the dark eerie forest, the gloomy lighting and the colonial dress. The refutation of didactic meaning, and the invitation to subjectively engage the image, is crucial for apprehending Welch’s art. It is also a common strategy of Romantic landscape painting.

Romantic landscape painting always sought to involve the viewer. If the landscape became an exteriorization of the painter’s interior, the landscape painting acted as a mirror of the viewer’s psyche. The viewer is required to add meaning to the Romantic painting if she wants to see more than just a landscape. Drawing on the conventions of Romantic landscape painting, Welch invokes the viewer’s engagement with the image. But she does so not to simply prompt a reflective, subjective, relationship with the image. Crucially, she also seeks to summon a critical, inquiring, gaze from her audience: one that bears a heightened sensitivity to the aesthetic tropes and motifs that occupy and give meaning to her images. For her works arrange these in familiar and unfamiliar – or better still uncanny – visual arrangements that work to disorientate our conception of the Australian landscape. We, the audience, must be attentive to the dynamics of Welch’s art.

Illuminations #1 portrays the Blue Mountains as an untouched “sacred wilderness”, adopting familiar Romantic aesthetic motifs such as the panoramic shot, an elevated view of the mountain, and an expansive horizon line. But a chandelier hovers at the centre forefront of the image, and obstructs this otherwise sublime image of the Blue Mountains. In Illuminations #1, and indeed in many of Welch’s recent works, the chandelier, an icon of European aristocracy since the 15th century, acts to signify European idealism and culture and its invariable mediation of our perception of the Australian landscape. Welch, in other words, seeks to make us self-reflexive about the European mediation of the Australian landscape that emerges as a consequence of British colonisation.

Welch’s work, which arises in the second decade of the 21st century, is indelibly affected by the legacies of postmodernism and postcolonialism. During the late 1970s, in light of the Indigenous civil rights movement in Australia, artists became increasingly aware of postcolonial politics, straying from white, colonial, traditions and conceptions of the nation’s history and identity. Simultaneously, Australian artists began to engage with theories of postmodernism, arguing that if culture is always a cultural construct, then the image of landscape – the painting, the postcard and photograph – must also be a fabricated, rather than a ‘realistic’ or ‘natural’ reflection of place. The Australian landscape tradition, as indigenous and non-indigenous contemporary Australian artists such as Rosemary Laing, Tracey Moffatt and Anne Ferran have revealed, is a cultural construction that projects colonialist, and often patriarchal, conceptions of the land.

Artists such as Laing and Moffatt have worked to unveil how the Australian landscape tradition worked to erase the presence and histories of indigenous Australians on the land. Meanwhile contemporary artists such as Ferran have focussed on tracing the faded histories of other disenfranchised colonial subjects, namely, convict women who were subject to forced labour at the Ross Female Factory in Tasmania and removed from any images of the Australian landscape. While for Welch, a postcolonial consciousness affects her own re-visitation of the Australian landscape tradition, like Ferran, she is particularly interested in the ghosted histories of female colonial subjects, particularly in Hill End, where Welch completed an artist residency in 2010, and shot the images for her triptych of self-portraits, Shedding of Time Immemorial, Terra Australia Incognita and Deliverance.

Perhaps at first glance Welch’s landscapes appear innocent, seductive even. But behind the brooding forest, misty skies and the thick of fog, the vanishing points of colonial histories await our attention. Today, the human psyche – which is always at the centre of the Romantic vision – is invariably affected by traumatic histories from the colonial era and the plight of those figures who still remain in the periphery, or buried deep, in the Australian psyche. Our period is haunted by the ghosts of the Stolen Generation and colonial genocide, and the shadowy figures of still largely uncharted colonial histories. Today, the sublime mountain range and the ominous sky do not simply conjure an awesome view of nature. As seen in Welch’s recent work, the landscape offers a means to reflect on the human interior in the early 21st century amidst the still lingering, colonial, past.

PHOTOGRAPHY & PRINTMAKING exhibition at the CBD Gallery, Sydney

1 February – 3 March

Selected is an opportunity to see into the practice of 22 contemporary artist exploring and thriving in using the medias of Printmaking and Photography across 52 images on display. Although printmaking and photography both originated from discrete technologies for example armour engraving for etching and camera Obscura for photography. They both could be seen to promote the same objective, the desire to replicate a vision of reality in multiples for commercial, political or journalistic ends. Whilst the objective of both disciplines is to leave a trace albeit figure, landscape or still life, the two had been used differently in the art world until the point when they were brought together.

2023

WEST OF CENTRAL at Bathurst Regional Art Gallery

1 July – 27 August

Home to an increasing cohort of contemporary artists and creatives seeking connection, respite, and balance, regional Australia is a place where artists have space to create, experiment, respond and challenge. This exhibition showcases the work of 17 regionally based artists who choose to make work on Wiradjuri Country in the Central Tablelands of NSW.

Of primary concern is the impact of man-made and climactic events on the ecologies and landscape of the region. A chaptered exhibition, to recur over multiple iterations, it celebrates artists who choose to live and work regionally, beyond an urban-centric ‘centre’ and in so doing resituate the regional as a core tenet of their practice.

From the Blue Mountains to Mudgee, Bathurst to Hill End and their surrounds, West of Central featured artists include Aleshia Lonsdale, Anne Graham, Bill Moseley, Blak Douglas, Caitlin Graham, Georgina Pollard, Genevieve Carroll, Dan Kojta, Jason Wing, Joyce Hinterding and David Haines, June Golland, Karla Dickens, Leo Cremonese, Maddison Gibbs, Nicole Welch, and Vicky Browne.

The Art of Analogue Part 1

It was a generous and warm gesture (welcome to Hill End!) when artist, photographer and generally cool person Bill Moseley asked me to talk about how I use an analogue process in unison with digital technologies. Intrigued? Click on the link below.

The Art of Analogue Part 1

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1-GrTn4Y1sc

“A presentation on making wet-plate collodion images, aka ‘tintypes’ in the historic town of Hill End. A town well know through the 1870’s Holtermann collection of glass plate negatives. In it, Bill Moseley explains the process and it’s context within on the world of Analogue. The video also features the work of Nicole Welch, and her comments on the significance of the analogue approach to art making.”

Beating About The Bush at the Art Gallery of Ballarat

November 5 – 19 February 2023

I’m honoured to have my work exhibited in Beating About The Bush at the Art Gallery of Ballarat which puts works of the Australian Impressionism era alongside works by contemporary Australian women photographers. Themes such as gender, hardship of life in the bush, immigration, urban growth, environmental concerns and the presence of Indigenous peoples are explored through the work of some of Australia’s most exciting contemporary artists.

It includes paintings from the past alongside contemporary photography: Donna Bailey, Jane Burton, Peta Clancy, Maree Clarke, Nici Cumpston, Tamara Dean, Fiona Foley, Deanne Gilson, Siri Hayes, Dianne Jones, Leah King-Smith, Rosemary Laing, Janet Laurence, Hayley Millar Baker, Jill Orr, Polixeni Papapetrou, Robyn Stacey, Jacqui Stockdale, Nicole Welch, Anne Zahalka

From the Studio, the Artists of Hill End

December to February 2023

A diverse range of artistic practices have flourished and continue to flourish in Hill End. I’m delighted to have an artwork in the group exhibition ’From the studio’, a window into the current artists residing in Hill End and their work.

2022

How a new art project in Bathurst is embracing the many identities of the town – ‘Wiradyuri Ngayirr Ngurambang – Sacred Country’ review in The Conversation by Suzie Gibson

“The most breathtaking project launched at the Mountain Tales event is Aunty Leanna/Wirribee and Nicole Welch’s collaboration with Smith, Wiradyuri Ngayirr Ngurambang – Sacred Country, a film emblazoned across Tremain’s Mill.”

LINK

https://theconversation.com/how-a-new-art-project-in-bathurst-is-embracing-the-many-identities-of-the-town-185860

Bathurst Winter Festival – Tremains Mill Bathurst

‘Wiradyuri Ngayirr Ngurambang – Sacred Country’ July 2022

Nicole Welch, Wiradyuri Elder Wirribee Leanna Carr-Smith, & Kate Smith.

An immersive moving image work exploring Wiradyuri Ngurambang Ngayirr. Wiradyuri Elder Wirribee shares part of the narrative of Custodianship of Country, collaboratively working with local Artist Nicole Welch’s work that is linked to care-taking the environment. This work explores shared understandings between First Nation and Non-First Nation women. Connecting to the landscape from Tarana along the Wambuul/Macquarie River to Wahluu/Mt. Panorama offering a space for contemplation toward a healing of people, community, place,and shared stories.

Yarrahapinni screening at the South Australian Museum

18 February 2022

Delighted that my work ‘Yarrahapinni’ 2019 is screening at the South Australian Museum Night Lab BEDTIME STORIES for the 2022 Adelaide Fringe

“You are about to enter another dimension, a dimension not only

of sight and sound but of mind, a journey into a wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination.”

2021

Nicole Welch

Interruptions and Illuminations

23 April – 14 May 2021

Artereal Gallery is excited to present Nicole Welch’s first online show with the gallery – a survey of select artworks produced over the last decade which encapsulate the essence of her practice.

LINK

https://artereal.com.au/online-exhibition/interruptions-and-illuminations/

Time Travel and Digital Art: How Nicole Welch’s Time-lapse Video Art Collapses Time – Agora Digital London – Elizabeth Harris | Ed Kiran Sajan

Making art does make me feel like a time traveller.

Thank you Agora Digital London, Elizabeth Harris and Kiran Sajan for this insight into my ongoing exploration of timelapse film, landscape and body. Agora Digital Art expands awareness of women in digital art – by profiling artists, sharing stories, offering virtual residencies and delivering talks.

Click on the LINK below to read the article

LINK

https://agoradigital.art/time-travel-and-digital-art-how-nicole-welchs-time-lapse-video-art-collapses-time/?fbclid=IwAR2TvQkkxQ2cDbDIDbP7_WC2ZR-u2_kX-HtX2bIckC5myp5xlNiJ96lXJ6I

REGIONAL ARTS FUND GRANT 2021 - REGIONAL ARTS NSW

Delighted that my future project AS ABOVE SO BELOW has been generously supported through the Regional Arts Fund – Regional Arts NSW.

“Artist Nicole Welch will record in photography and moving image her reconnection to the natural world in response to ongoing isolation imposed by COVID-19. She will develop new techniques through the exploration of macro and micro photography to make new installations and performances for her LAND & BODY series of work, across sites at the Macquarie and the Lachlan Rivers. The outcomes of AS ABOVE, SO BELOW will be exhibited at the Orange Regional Gallery and MAY SPACE Sydney.”

・・・

Congratulations to the 18 artists and organisations who have received RAF project funding to support new projects across NSW in 2021! RANSW CEO, Elizabeth Rogers said: ” Once again, the calibre of these projects supported by the Regional Arts Fund in NSW showcases the creativity of our regional arts organisations from across the state.”

2020

The CORRIDOR Project Artist Residency 2020 (November)

Just home from a special kind of isolation at the CORRIDOR Project at Darby Falls near Cowra NSW undertaking an artist residency.

The CORRIDOR project is a multidisciplinary arts organisation located in regional NSW Australia. The 2020-2021 Arts and Science program links arts & culture and science, through residencies; events and workshops.

I am extremely grateful to the CORRIDOR project manager Phoebe Cowdery, the CORRIDOR patrons Andrew Upton and Cate Blanchett, the Orange Regional Gallery and the various funding bodies that have supported the residency program for 2020.

SYDNEY CONTEMPORARY PRESENTS 2020 • MAY SPACE

I’m grateful to be presenting my moving image work Yarrahapinni at Sydney Contemporary’s first online fair with MAY SPACE - alongside the wonderful Todd Fuller, Mylyn Nguyen, Catherine O’Donnell, Janet Tavener and Loribelle Spirovski.

See this link for full access to the 450 artworks, 380 artists, and 90 galleries participating this year!

https://sydneycontemporary.com.au/scpresents/

!!

Yarrahapinni (preview) 2019

single channel HD infrared time lapse – 3:21mins

50 inch screen, gilded frame edition of 3

The CORRIDOR artist-in-residency program 2020 (May)

The last morning of my preliminary artist residency in complete blissed out isolation at the CORRIDOR PROJECT in the Central West of New South Wales as part of the CORRIDOR artist-in-residency program 2020. The dramatic change in the landscape and natures resilience is inspiring to me – so green after such a long dry spell. It has been an invaluable time to explore new media, techniques and ideas for a new body of work to be exhibited at the Orange Regional Gallery – a welcomed break from home ISO - it has started a ball rolling, thank you

Kangaroo Valley Art Prize

The moving image work Yarrahapinni has been selected as a finalist in the Kangaroo Valley Art Prize.

ArtsHub Review by Gina Fairley

Manly Dam Project

Manly Art Gallery (NSW)

LINK

https://visual.artshub.com.au/news-article/reviews/visual-arts/gina-fairley/manly-dam-project-manly-art-gallery-nsw-259532?fbclid=IwAR2CB3gSZnylmOJt96wJzPKfWMiKPmMryygPvJFN5ZyXi2HSEHk-bcob1vI

Listening to the Anthropocene

Yarrahapinni has been selected/peer reviewed for the 2020, Charles Sturt University Creative Practice Circle symposium and exhibition entitled Listening in the Anthropocene: Creative practice and multimedia artsmaking in response to a human influenced world.

2019

Manly Dam Project

Altered States – Tamara Dean & Nicole Welch

Naked & Nude Art Prize

TRANSFORMATION selected as a finalist in the Naked & Nude Art Prize at the Manning Regional Art Gallery.

Sydney Contemporary Art Fair 2019

New work ‘W I L D #1 – prelude’ exhibited at the MAY SPACE booth, G09

Stillness & Motion – Nicole Welch – Adelaide Perry Gallery

Select photographic works and film from the past 5 years.

2 – 24 May 2019

Nicole Welch By Artist Profile

LINK

https://www.artistprofile.com.au/nicole-welch/

2018

Making it as a regional artist – the realities and the wins

ArtsHub visual arts editor Gina Fairley’s feature editorial on Nicole Welch for ArtState Bathurst

Transformation – arrival, installed at Tremains Mill for ArtState Bathurst 2018

LINK

https://visual.artshub.com.au/news-article/features/visual-arts/gina-fairley/making-it-as-a-regional-artist-the-realities-and-the-wins-256839?utm_source=ArtsHub+Australia&utm_campaign=94d6aaf38a-UA-828966-1&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_2a8ea75e81-94d6aaf38a-304113053&fbclid=IwAR0TLXyOknKMReZDiSmTininEpoQzMUx_tPjD53llAkUd4W-opQEluYa9jo

5th International Motion Festival, Cyprus

The time-lapse film Wildēornes Body has been selected for the 5th International Motion Festival, Cyprus. It will feature in the Single Channel Show (Video Art presented with single channel works. Experiments pushing the limits of the moving image)

Wildēornes Body (still) 2017

Nicole Welch – Black Box Projects 2018

To coincide with Nicole Welch’s presentation of the moving image work Transformation and photographic series Mementos at Artstate Bathurst (1 to 4 November 2018), as well as her solo exhibition Silence & Solitude: select works from Eastern Interiors at Glasshouse Regional Gallery (12 October to 2 December 2018), MAY SPACE is presenting a selection of Welch’s video artworks in Black Box Projects.

Transformation: the prelude (preview)

TRANSFORMATION unveiled at ArtState Bathurst 2018

Nicole Welch’s most ambitious project to date was a featured part of Artstate Bathurst 2018. The two-channel video work sees a female figure carefully moving through the landscape.

Transformation – journey, installed at Tremains Mill for ArtState Bathurst, 2018

MEMENTOS ArtState Bathurst 2018

Nicole Welch was chosen to create a small gift for the delegates that attended Artstate Bathurst 2018. The resulting series of infrared photographs were packaged up in miniature for the guests. Full-scale versions are now available from MAY SPACE.

Mementos #3 – Macquarie River 2018

LINK

https://www.mayspace.com.au/exhibitions-details/nicole-welch-artstate-bathurst

ArtsHub Review by Helen Wyatt

Review: Jason Wing and Nicole Welch, 4.5 stars, Glasshouse Regional Gallery

Silence & Solitude: select works from Eastern Interiors

GlassHouse Regional Gallery, Port Macquarie

Silence & Solitude exhibition at GlassHouse Regional Gallery

LINK

https://visual.artshub.com.au/news-article/reviews/visual-arts/helen-wyatt/review-jason-wing-and-nicole-welch-glasshouse-regional-gallery-256707?fbclid=IwAR0g8PuwkcQ2unOv13l2bM1MLLG9zGF6sC4Irex4TzE8Pz_R7QcQaUD83_k

Media artist Nicole Welch explores the colonial history of the Blue Mountains in exhibition at The Glasshouse

Port Macquarie News

Nicole Welch at the GlassHouse Regional Gallery 2018

LINK

https://www.portnews.com.au/story/5699463/silence-and-solitude-exhibition-reflects-on-colonial-past/?fbclid=IwAR2zdbJTsz0B6nBMwIxH63HfMTU2ZtMRSOYZxeeJg_nQgcZMiTR9xJWhUXA

Transformed by Place: Q&A with Artstate Artist Nicole Welch

An interview with Nicole Welch about TRANSFORMATION and MEMENTOS commissioned for ArtState NSW 2018

LINK

http://www.artstate.com.au/transformed-by-place-qa-with-artstate-artist-nicole-welch/

Finalist Grace Cossington Smith Art Prize 2018

Three photographs from the Wildēornes Land series have been selected for the Grace Cossington Smith Art Prize 2018

Wildēornes Land #1 – Capertee Valley 2017

Wildēornes Land #3 – Grose Valley 2017

Wildēornes Land #7 – Wollemi 2017!

ArtState Bathurst 2018

Nicole Welch is producing two new works TRANSFORMATION and MEMENTOS for ArtState Bathurst NSW Regional Arts Conference, Create NSW, 2018

Transformation: the prelude screened at Sydney Contemporary Art Fair 2018

Nicole Welchs latest moving image work Transformation : the prelude was unvieled at the Sydney Contemporary Art Fair 2018. Constructed from 1000 photographs of a waterfall captured using infrared technology, the resulting hyperreal light spectrum and colours revealed are invisible to the human eye, symbolically referencing the notion of the unobserved

Transformation: the prelude (preview)

2017 + PRIOR

WILDĒORNES LAND 2017

Wildēornes Land

by Dr. Ann Finegan

Co-Director Cementa Contemporary Arts Festival

Interrogations of European notions of the sublime in nature, colonialist mastery and ecology subtend the cinematic imaginary of Nicole Welch. In Wildēornes Land she subverts another Eurocentric concept brought to Australian shores: the wilderness of European folklore. Steeped in the dark lore of the forest – its haunted zones, domains of witches, its dens of wolves and shapeshifters – European folktales persist in many of the stories handed down. The Brothers Grimm, Hansel and Gretel, Sleeping Beauty, Little Red Riding Hood. When the European colonists arrived in Australia they also brought with them this dark imagery. Deep in the European psyche, bad things happen to people in the woods. The wilderness is therefore the place that you don’t go – certainly not unarmed or lacking talismans. It is a place of extreme vulnerability. Even for Indigenous Australians there are places of bad spirits, places that command ceremonies of appeasement. Unless, of course, you are on a peak, looking down, surveying the vastness of the scary place from the other side of a magical divide.

The importance of the vantage point cannot be underestimated. Without it, the vast and daunting scale of the ‘Wildēornes’ cannot be enjoyed through the European colonialist lens. The vantage point, drawing its line of demarcation between known and unknown, savage and civilized, safe and unsafe, underlies the lesson of the sublime in nature: terrifying chasms and dangers tamed through the imaginary possession of the view from on high, from that point of Kantian safety. In Wildēornes Land something has shifted. Nature is no longer secure. With climate change the big scary wilderness has lost its power. Welch, naked, in an antique mourning shawl, stands on a sublime Blue Mountains abyss. She occupies the same position as Caspar David Friedrich’s confident wanderer, immaculate in his 18th century gentleman’s suit, surveying a mighty realm. Welch, by contrast, in mourning garb, offers herself, naked and sacrificial, to a world on the brink of being lost. The symbolism of Welch’s composition asks us to imagine the unimaginable: an ecological crisis that dwarfs the wilderness that was, once, for Europeans, our deepest repository of fear. Across images of clouds and sky, at cinematic scale, that same delicate black mourning shawl suspends itself, its pall a symbol of human making heralding death. It epitomises the Victorian era as the departure point from which the industrial revolution and the burning of fossil fuels accelerated. Like the gaseous changes taking place in the atmosphere there’s a gossamer lightness to it.

Tondo #4, Projection – Regent Honeyeater from ‘The Birds of Australia: in seven volumes’, John Gould, 1848, 2016

In the tondi, exquisitely framing the landscape through the circular aperture of an 18th century aesthetic, something is clearly wrong. The sky dominates. It’s as if there’s been an accident, someone has bumped the camera, skewing the subject. Instead of rare birds holding the focus in Tondo #4, Projection – Regent Honeyeater (2016), or the view from the lookout garnering attention, Tondo #3, Kanangra Wall Lookout (2014), the sky intrudes at odd angles, somehow menacing. Where the wilderness once dominated, lurking in the psyche, the carbon-saturated atmosphere has become the new sublime of danger.

Artlink Review

Nicole Welch: Wildēornes Land

Blue Mountains Cultural Centre

Wildēornes Land installed at the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre City Gallery 2017

LINK

https://www.artlink.com.au/articles/4590/nicole-welch-wildC493ornes-land/

EASTERN INTERIORS: EXPLORATIONS FROM BATHURST TO ALBURY 2015

Forward Reflections

by Olivia Welch (not related to the artist)

Notions of ‘beauty’ and ‘sublimity’ are conjured when encountering the photographic and video work of Nicole Welch. Though it could be instinctive in the twenty-first century to consign the exceptional picturesque appeal of these works to a mastery of digital manipulation, Welch does not depend on such techniques. Instead, the artist traverses through areas of bushland, locating incredible landscapes to create compositions using large-scale projectors, generators, spotlights and research-inspired objects. These works have seen Welch interrupt the rugged terrain with illuminating beams of light, projections of images and a chandelier that is seemingly floating in the landscape, despite actually being hoisted into the scene using a crane. In the suite of images that formulate Eastern Interiors: explorations from Bathurst to Albury new iconography emerges with the inclusion of an antique mirror and the use of text.

There is an archival foundation to Welch’s hybrid imagery. The landscapes within her photographs do not simply exist as visually attractive images, but engage with the history of ‘landscape’ as a creative genre, whilst also integrating interpretations of the land from literature, exploration records and other resources. Her series Illumination featured a luminescent Victorian-style chandelier, taking cues from archival research into the historic Holtermann Collection; a series of photographs made by Beaufoy Merlin and Charles Bayliss in 1872. Welch’s 2014 body of work Apparitions featured circular details of paintings from the Romantic period, found in the collections of the National Gallery of Australia and the Art Gallery of New South Wales, projected onto waterside cliffs and foggy forest scenery. Eastern Interiors: explorations from Bathurst to Albury references Explorer Thomas Mitchell’s journals originally published in 1838 under the title ‘Three expeditions into the interior of Eastern Australia’, a first edition of which can be found in the collection of the State Library of New South Wales. Mitchell was the Surveyor General of New South Wales and his role was to manage and administer Crown Land; defining boundaries, locating places for new settlements and planning routes for transportation. This job entailed lengthy expeditions across the country, often requiring the assistance of Indigenous guides. Through these journeys, land was divided and defined by the colonial settlers in ways that suited their Eurocentric needs and opinions. These decisions and descriptions shape our knowledge, understanding and perception of the land today, a theme that Welch aptly draws attention to.

Comparably to Mitchell, Welch embarked on a cross-state expedition in order to (re)discover the locations within her latest series of work. Informing the suite is a residency the artist completed in September of 2014 at Hill End near Bathurst, as well as time spent in and around Albury in the State’s south. The video work that completes this series, titled ‘East West’, references the travelling nature of Welch’s research, as well as the explorers she quotes. It features a mirror reflecting the sky as it transitions from day to night, communicating the role of the sky as a global and perpetual navigational device.

East West (still) time-lapse film 2015

East West (still) time-lapse film 2015

Welch is originally from Bathurst and is currently based there, making her connection both personal and physical. A group of works in Eastern Interiors: explorations from Bathurst to Albury is titled ‘Frightful Tremendous Pass’. The group takes its name from a 200-year-old quote within Governor Macquarie’s journals that was written while he was travelling to proclaim Bathurst as a settlement of the colony. As the Governor’s journal reads, “At 11 o’clock, (we) reached the termination of the Blue Mountains… to view this frightful tremendous Pass.” In the context of these diaries that also describe one area as “very bad” for cattle and carriages, and the soil quality of Bathurst as “…fit for every purpose of Cultivation and Pasture…”, it is easy to see how these descriptions of the Australian terrain are based upon what was seen as useful and/or beautiful to European needs and preferences.

In the second and third work of the ‘Frightful Tremendous Pass’ set, Welch plays with Governor Mitchell’s accounts. The artist ironically projects Mitchell’s idea of tremendousness and frightfulness via literal projections. The word “Tremendous” is cast onto a plateau girt by water at the edge of the Blue Mountains, and the word “Frightful” is contained within a nocturnal scene, illuminated over a bed of ferns surrounded by tall native trees. These observations powerfully punctuate their respective landscapes, causing associations between the meanings of these words and Welch’s carefully orchestrated environments to merge- revealing the impressionability of such emotive language. Similarly, the set of works titled ‘Silence and Solitude’ is influenced by Governor Macquarie’s following musing: “…the silence and solitude, which reign in a space of such extent and beauty as seems designed by nature for the occupancy and comfort of man, create a degree of melancholy in the mind…” In one of the works, Welch has projected the word “Solitude” onto a misty landscape. This work remains the most sinister image of the suite, ghostly in its effect. With all of these photographs, Welch cleverly embodies both hostile and inviting environments with historical descriptions that label the conditions in which the colonial settlers encountered them.

Taking their titles from words within William Hovel’s journal, which relays his explorations to find new grazing land with Hamilton Hume in 1824, are Welch’s works given the common title ‘Magnificent Prospect’. Describing an impressionable sight of the Snowy Mountains near Albury, Hovell writes, “At the end of seven miles a prospect came in view the most magnificent.” Featuring a mirror reflecting the landscape opposite the scene in which it is situated, these photographs project magnificence in their striking appearance. This set includes an eerie fog-filled scene where the trees seemingly dissolve into an encroaching distance, as well as a brilliant blue sky striped with fluorescent sun-soaked clouds that are disrupted by the reflection of pastel pink heavens glowing behind a rocky cliff. These captivating environments are wondrous, yet diverse, evoking the idea of endless possibilities for Hovell’s new “prospect”, a label that also coveys a sense of adventure and discovery designated to a land not yet captured or claimed.

Though it is easy to relegate notions of Australia being an unclaimed wilderness to an archaic imperialist past, Welch reveals how the consequences of this ideology have seeped into contemporary society’s relationship with the Australian landscape. The artist references a quote from theorist W. J. T. Mitchell’s essay ‘Imperial Landscape’, which reads, “Like all things in a rearview mirror, these landscapes may be closer to us than they appear.” Welch’s works containing mirrors draw from this quote by literally placing a mirror in the landscape. In each work, the reflection is contained within an antique frame that acts like a portal into the past. Through this, Welch exposes the contemporary desire to view the Australian terrain via a nostalgic lens, which romanticises the landscape as an undiscovered place of mystical beauty and inhospitable depths. However, this romantic mythology is ruptured, as the mirror lies within the landscape it reflects, showing that both the evocative view in the frame, and the perceptibly present-day terrain surrounding it, coexist.

Throughout Eastern Interiors: explorations from Bathurst to Albury, the past and present are conflated in singular images and filmic scenes. With this, Welch subtly offers a thoughtful examination on how contemporary perceptions of the natural Australian landscape continue to be shaped and informed by enduring historical ideologies.

APPARITIONS 2014

ILLUMINATION 2012

Anachronism, Romanticism and the Australian Landscape Today: Nicole Welch’s Illuminations (2012)*

by Veronica Tello

Terra Australis Incognita from the Self series, Hill End 2010

Deliverance from the Self series, Hill End 2010

The European, colonial, representation of the Australian landscape, which is the subject of Nicole Welch’s recent work, first appears in the journals and sketches of the officers of the First Fleet. These eighteenth century colonialists drew upon the language and aesthetic tropes of the arcadian tradition to describe and detail the new world. Through the eyes of British colonialists, Australia was always seen in terms of its potential for colonisation, for building an arcadia. The European arcadian tradition would continue to define our perception of the Australian landscape throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The British émigré John Glover and the German émigré Hans Heysen, amongst other artists including the Heidelberg School, worked to emphasise the fertile and arcadian Australian pastures, which shone under the brilliant Australian sun and its blue skies. In Bathurst, and the regions of the Blue Mountains, Hill End and Sofala, which are the focus of the landscapes in Welch’s recent work, John Lewin similarly sought to articulate the pastoral potential of this land. Since the arrival of the First Fleet, the pastoral tradition has dominated our conception of the Australian landscape. But as Welch seems to suggest, there is a distinct, somewhat neglected, European conception of the Australian land to which we must attend. Invoking elevated mountain views, expanded horizons, brooding forests and dramatic saturated ominous skies Welch picks up on the European landscape tradition of Romanticism and critically attends to how this aesthetic affects our conception of the Australian landscape today.

The artistic movement of Romanticism finds its roots in late 18th century Europe and manifests in a variety of art forms from poetry to portraiture, and most importantly, landscape painting. As Caspar David Friedrich, the most famous proponent of Romantic landscape painting claimed, via artistic representations, Romanticism aimed to exteriorize the human interior, that is, human emotions and the human psyche. Revolting against the restrictive rationalism of the Enlightenment era, the Romantics turned to nature and what they perceived to be its irrational, untameable and awe-inspiring forces to conjure ambient atmospheres that would reflect interior feeling. For the Romantics, the boundless sky, the tumultuous and expansive ocean, the lofty and terrifying mountains represented the unfathomable and terrifying power of nature that would come to dwarf man. Giving preference to dramatic and moody nighttime scenes as well the glimmering morning light, the Romantics felt that these enigmatic transitional moments of twilight evoked the darker conditions of the human condition.

Some critics argue that Romanticism first emerged in Australia in the mid 19th century via the Austrian émigré painter Eugene Von Guérard and his epic panoramic landscapes, as seen in Govett’s Leap and Grose River Valley, Blue Mountains, New South Wales (1873). But the recent exhibition Eugene Von Geurard: Nature Revealed (National Gallery of Victoria, 2011) has shown that Von Guérard was, in fact, thoroughly influenced by Alexander Von Humboldt’s scientific, rationalising, theories of nature. Perhaps, then, it was not until the emergence of the moody, awe inspiring, panoramic landscapes by the wilderness photographer Peter Dombrovskis that a Romantic aesthetic came to properly occupy the Australian imagination. Welch’s recent art, adopts similar aesthetic tropes to those that are found in the photography of Dombrovksis and the 19th century Romantic landscape painters. Throughout her new series of photographs titled Illuminations, Welch adopts panoramic vistas, an elevated view of a dark brooding mountain range, enigmatic and transitional lighting, and crucially, in a series of self-portraits, she presents herself with her back turned to the audience.

If humans were ever presented within the Romantic landscape, they remained anonymous silhouettes, most often with their backs turned to the viewer, so that she may freely identify with the landscape rather than human subject. In Shedding of Time immemorial the trees and the deathly still night encroach on a solitary vulnerable figure. Welch stands idly unveiling her body and removing a colonial dress. In Terra Australia Incognita and Deliverance, the figure appears naked, exposing the black skeletal patterns that mark her flesh. She appears to be in between worlds – between now and then, between here and there, between life and death. Keeping her back turned to the audience, this mysterious figure imbues these images with a striking privacy and enigma. For while it is clear that we, the audience, are invited to look on, our capacities to read the image are contingent on our abilities to engage its details. The triptych is filled with a range of visual cues that compel us to activate a subjective narrative. We are prompted to ascertain a meaning by thinking through the relations between the mysterious naked figure, the skeletal drawing, the dark eerie forest, the gloomy lighting and the colonial dress. The refutation of didactic meaning, and the invitation to subjectively engage the image, is crucial for apprehending Welch’s art. It is also a common strategy of Romantic landscape painting.

Romantic landscape painting always sought to involve the viewer. If the landscape became an exteriorization of the painter’s interior, the landscape painting acted as a mirror of the viewer’s psyche. The viewer is required to add meaning to the Romantic painting if she wants to see more than just a landscape. Drawing on the conventions of Romantic landscape painting, Welch invokes the viewer’s engagement with the image. But she does so not to simply prompt a reflective, subjective, relationship with the image. Crucially, she also seeks to summon a critical, inquiring, gaze from her audience: one that bears a heightened sensitivity to the aesthetic tropes and motifs that occupy and give meaning to her images. For her works arrange these in familiar and unfamiliar – or better still uncanny – visual arrangements that work to disorientate our conception of the Australian landscape. We, the audience, must be attentive to the dynamics of Welch’s art.

Illuminations #1 portrays the Blue Mountains as an untouched “sacred wilderness”, adopting familiar Romantic aesthetic motifs such as the panoramic shot, an elevated view of the mountain, and an expansive horizon line. But a chandelier hovers at the centre forefront of the image, and obstructs this otherwise sublime image of the Blue Mountains. In Illuminations #1, and indeed in many of Welch’s recent works, the chandelier, an icon of European aristocracy since the 15th century, acts to signify European idealism and culture and its invariable mediation of our perception of the Australian landscape. Welch, in other words, seeks to make us self-reflexive about the European mediation of the Australian landscape that emerges as a consequence of British colonisation.

Welch’s work, which arises in the second decade of the 21st century, is indelibly affected by the legacies of postmodernism and postcolonialism. During the late 1970s, in light of the Indigenous civil rights movement in Australia, artists became increasingly aware of postcolonial politics, straying from white, colonial, traditions and conceptions of the nation’s history and identity. Simultaneously, Australian artists began to engage with theories of postmodernism, arguing that if culture is always a cultural construct, then the image of landscape – the painting, the postcard and photograph – must also be a fabricated, rather than a ‘realistic’ or ‘natural’ reflection of place. The Australian landscape tradition, as indigenous and non-indigenous contemporary Australian artists such as Rosemary Laing, Tracey Moffatt and Anne Ferran have revealed, is a cultural construction that projects colonialist, and often patriarchal, conceptions of the land.

Artists such as Laing and Moffatt have worked to unveil how the Australian landscape tradition worked to erase the presence and histories of indigenous Australians on the land. Meanwhile contemporary artists such as Ferran have focussed on tracing the faded histories of other disenfranchised colonial subjects, namely, convict women who were subject to forced labour at the Ross Female Factory in Tasmania and removed from any images of the Australian landscape. While for Welch, a postcolonial consciousness affects her own re-visitation of the Australian landscape tradition, like Ferran, she is particularly interested in the ghosted histories of female colonial subjects, particularly in Hill End, where Welch completed an artist residency in 2010, and shot the images for her triptych of self-portraits, Shedding of Time Immemorial, Terra Australia Incognita and Deliverance.

Perhaps at first glance Welch’s landscapes appear innocent, seductive even. But behind the brooding forest, misty skies and the thick of fog, the vanishing points of colonial histories await our attention. Today, the human psyche – which is always at the centre of the Romantic vision – is invariably affected by traumatic histories from the colonial era and the plight of those figures who still remain in the periphery, or buried deep, in the Australian psyche. Our period is haunted by the ghosts of the Stolen Generation and colonial genocide, and the shadowy figures of still largely uncharted colonial histories. Today, the sublime mountain range and the ominous sky do not simply conjure an awesome view of nature. As seen in Welch’s recent work, the landscape offers a means to reflect on the human interior in the early 21st century amidst the still lingering, colonial, past.